-

Health & Wellness

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Diagnosing celiac disease not always a one-step process

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: My blood test for celiac disease came back negative, but I am still having symptoms. Is it possible that I still could have it? What should my next steps be?

ANSWER: The symptoms and presentation of celiac disease can vary quite a bit from one person to another. The most common symptoms are bloating and weight loss. Diarrhea or constipation may also affect some people. Less commonly, patients may experience an itchy, burning rash, called dermatitis herpetiformis, as well as heartburn, headaches, fatigue and joint pain, among others.  Celiac disease may also cause iron deficiency anemia and neuropathy — tingling or pain in the feet and hands that doesn’t go away. Eventually, if left untreated, celiac disease may cause damage to the nervous system, bones, brain, liver and other organs.

Celiac disease may also cause iron deficiency anemia and neuropathy — tingling or pain in the feet and hands that doesn’t go away. Eventually, if left untreated, celiac disease may cause damage to the nervous system, bones, brain, liver and other organs.

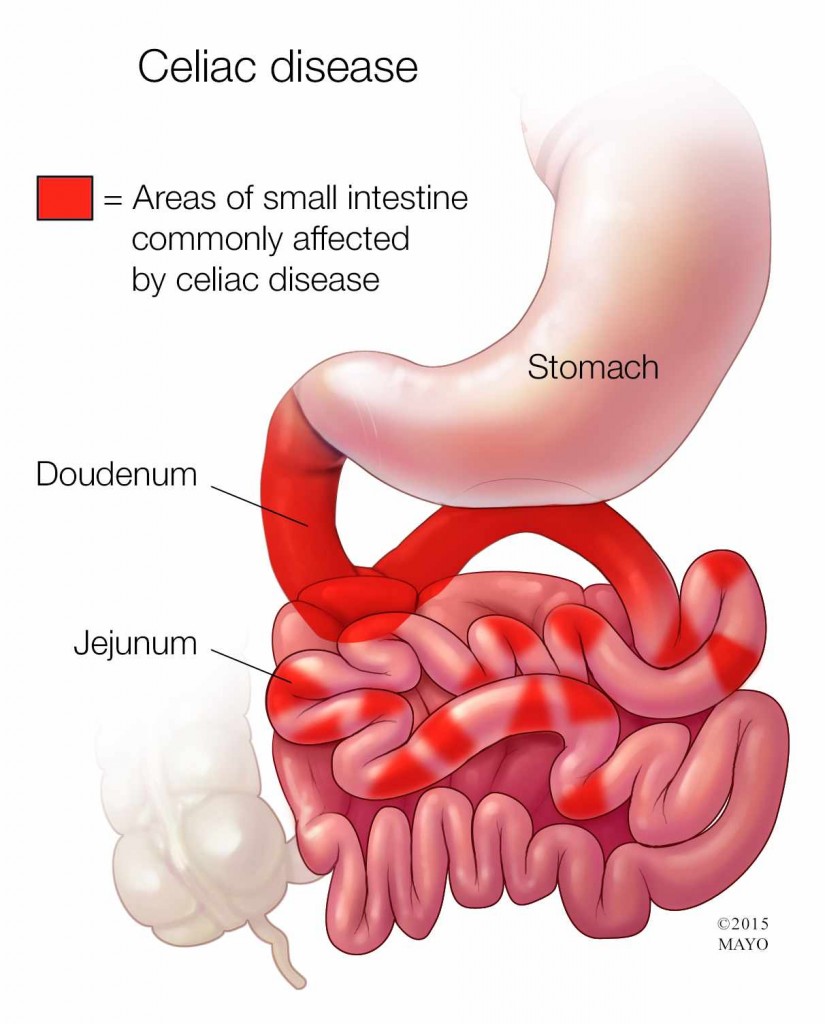

If you have celiac disease, eating gluten — a protein found in wheat, barley and rye — triggers an immune response in your small intestine that leads to inflammation. Over time, that inflammation damages the lining of the small intestine, making it difficult for the small intestine to absorb some nutrients.

Diagnosing celiac disease is not always a one-step process. It is possible that you could still have celiac disease, even if the results of an initial blood test are normal. Approximately 10 percent of people with negative blood tests have celiac disease. Additional testing can provide more information and give you and your doctor a better understanding of what may be causing your symptoms.

Diagnosing celiac disease typically begins with blood tests. It’s very important that the tests be done before you try a gluten-free diet. Taking gluten out of your diet before you have the blood tests may change the results so that they appear to be normal, even if you do have celiac disease.

The main blood test used for celiac disease checks for antibodies to an enzyme found in the lining of the intestine called tissue transglutaminase, or tTG. In about 3 percent of the population, however, the tTG test does not tell the whole story. That’s because when blood is drawn for the tTG test, levels of a substance called immunoglobulin A, or IgA, also are checked. If you have low or absent IgA, then the blood test is not reliable and other blood tests need to be done or an upper endoscopy may need to be performed.

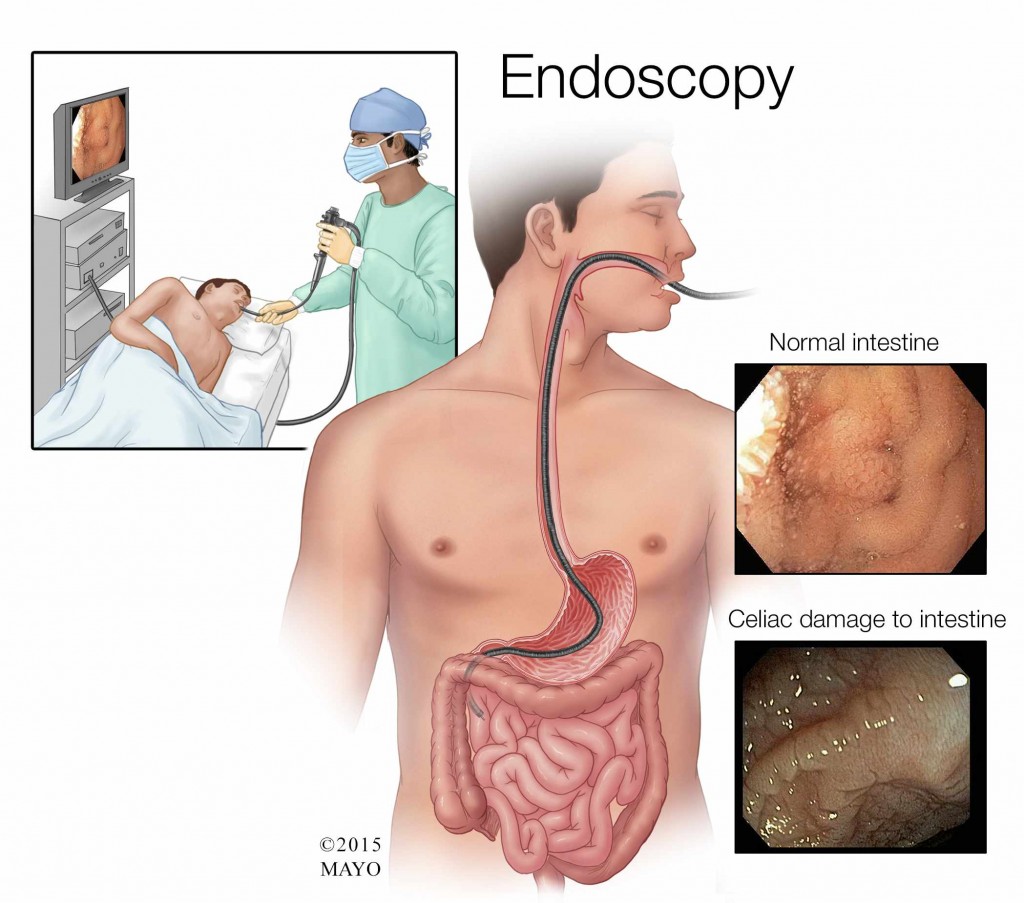

An upper endoscopy is performed using gentle sedation. It involves inserting a long, flexible tube, called an endoscope, down your throat and into your esophagus. A tiny camera on the end of the endoscope allows your doctor to see your esophagus, stomach and the beginning of your small intestine.

During the endoscopy, your doctor may take several tissue samples — this is called a biopsy. Those samples are later examined under a microscope to see if they show any damage. In particular, damage to the tiny finger-like projections that line the small intestine, called villi, may be a sign of celiac disease.

If the endoscopy and biopsy don’t reveal any damage, then it’s possible your symptoms are being caused by another medical condition. For example, some people have gluten sensitivity that is not related to celiac disease. In others, symptoms similar to those caused by celiac disease may be triggered by intolerance to carbohydrates. Additional testing typically is needed to identify other possible underlying causes.

In a situation like yours, it can be useful to seek care from a physician who specializes in celiac disease to further investigate the cause of your symptoms. You also may find it helpful to work with a dietitian, whether you are diagnosed with celiac disease or not. He or she can assess your diet and identify changes that may help ease your symptoms. — Lucinda Harris, M.D., Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz.

Related Articles