-

Health & Wellness

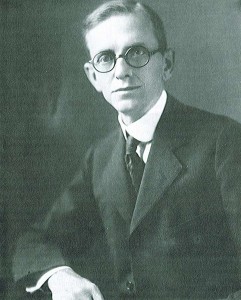

#ThrowbackThursday: Dr. Henry Plummer, Mayo’s ultimate Renaissance man

This article first appeared April 1989 in the publication Mayovox.

(Editor’s Note: The following article is adapted from a speech delivered by Robert Fleming, chairman of the Department of Administration, at the annual Supervisors’ Dinner on March 7, 1989.)

Mayo Medical Center employees who use the Mayo patient record or the pneumatic tube system, or who work in the Plummer Building, all have one thing in common: their working lives are touched each day by the contributions of one brilliant man, Dr. Henry Plummer. With the exception of Drs. Will and Charlie Mayo no one has left as significant an imprint on Mayo Clinic as the unforgettable Dr. Plummer.

The son of a country physician, Dr. Plummer was born near Racine, Minnesota in 1874. Though as a child he was most interested in mechanical devices and wanted to pursue engineering, he yielded to his father’s desire and studied medicine instead. Following graduation from Northwestern, Dr. Plummer returned to join his father’s practice in Racine.

But Dr. Plummer’s interest in engineering never waned. For example, while practicing country medicine by horse and buggy, he devised a system of ropes extending from his house to the barn. A feeding device at the end of the ropes allowed him to tug on the rope so that his horse would be fed a ration of oats by the time he was ready to leave on house call.

Dr. Will Mayo once remarked that the hiring of Dr. Plummer was the best day’s work he ever did for the clinic. When he joined the Mayo staff in 1901, Dr. Plummer took charge of bringing the laboratories up to date. A forerunner in the development of X-ray diagnosis and therapy, he also took charge of the clinic’s x-ray work.

Though his primary medical interest involved his pioneering work on the thyroid gland, Dr. Plummer’s understanding of medicine as a whole led to many other “firsts.” Some of these include development of mechanical methods of removing foreign bodies from the esophagus, development of bronchoscopy to remove foreign bodies in the bronchi and development of a method of diagnosing lung disease by removing specimens of lung tissue for examination under a microscope.

But Dr. Plummer’s energy could not be confined to the practice of medicine. During the decade from 1900 to 1910 as the Mayo reputation grew and the shortage of space for the busy clinic became acute, the Mayo brothers considered a new building designed especially for the group’s needs. As chairman of the Building Committee, Dr. Plummer assumed responsibility for the office and examining –room arrangements.

In his book, Forty-Four Years with the Mayo Clinic, Harry Harwick recalled that Dr. Plummer refused to draw plans until the Mayo group decided how they wanted to practice. Because of wide disagreement, Dr. Plummer went away for a few weeks to study the issue for himself. He returned with an armful of looseleaf notebooks in which he had charted the integrated practice that Mayo Clinic, and many other medical institutions, still follow.

“I recall instances of his farsightedness,” Harwick wrote. “For example, in 1910 the Mayo practice was overwhelmingly surgical. Dr. Plummer advised his colleagues to thin carefully since he predicted that, if his plans were adopted, within five years surgery would represent only about 35 percent of the gross volume of the institution’s work. This prediction was understandably derided, but he was wrong in only one respect. His prediction came true in three, not five, years.”

Dr. Plummer also was a genius in mechanical detail. The first clinic building, the red 1914 Building (where the Siebens Building now stands) was essentially his work. The architects gratefully acknowledged his leadership. The present Plummer Building, a work of art in the Moorish-Gothic style, is his monument. It is evidence of his inspired knowledge and wisdom.

Other innovations advanced by Dr. Plummer include:

- The clinic’s medical record system. He based it on the then-radical concept that the clinical data belonged not solely to the doctor who recorded them, but to the group. The system became a model for medical record keeping which, even with today’s computer technology, is essentially unchanged.

- The pneumatic tube system for sending patient histories underground from the clinic building to Saint Marys Hospital.

- The color-coded lights outside exam rooms that indicate the need for special consultants.

- The clinic’s conveyor system, a vital link in its communication network.

Dr. Plummer also was prominent in the design and construction of the Franklin Heating Station, and it was through his efforts that Rochester became Minnesota’s first city to be served by natural gas.

As an early partner of the Mayos, and later as a member of the Board of Governors, Dr. Plummer’s philosophy greatly influenced the concept of private group practice for which Mayo has become renown. The design of Mayo Clinic, based largely on his own ideas, became a prototype that has been widely copied.

On the afternoon of December 31, 1036, Dr. Plummer became ill with cerebral thrombosis. He recognized the nature of his illness and accurately predicted the outcome. He died that evening.

In reflecting on Dr. Plummer’s contributions to Mayo, Dr. F. A. Willius said in December 1953: “Thus, we glimpse a great man of high ideals and purposes, a profound thinker, a man of amazing concentration, and one with the rare gift of scientific imagination and the determination to carry projects to their successful conclusion.

“His knowledge had many facets and of each he was a master. Great men like Henry Plummer must not be forgotten because they are part and parcel of the traditional fabric of the Mayo Clinic.”

At Mayo, Dr. Henry Plummer will never be forgotten.

Related Articles