-

Treating more than the disease: Giving kids with cancer Brighter Tomorrows

While survival rates continue to improve, going through treatment can be incredibly difficult for children dealing with cancer and their families. But organizations that focus on lifting the spirits of patients and their families and helping them stay positive during treatment have become a welcome part of the treatment process. Often, these organizations dramatically affect outcomes.

Connor Johnson and his family think an organization called Brighter Tomorrows that helped them keep a positive outlook during his cancer treatment is one of the main reasons the 15-year-old is now cancer-free.

Watch: Treating more than the disease: Giving kids with cancer Brighter Tomorrows

Journalists: Broadcast-quality video pkg (7:00) is in the downloads. Read the script.

Few 15-year-old kids are as excited to start high school as Connor Johnson was. Less than two years earlier, he and his parents didn't know if he would ever get the chance to.

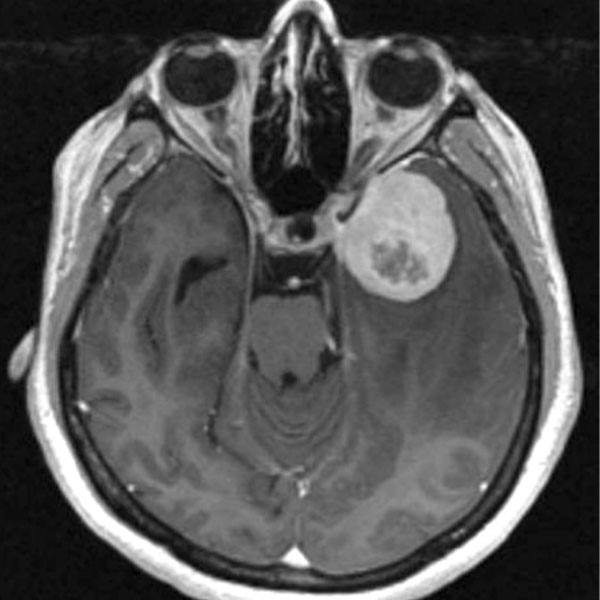

"I was 13 and we went in for an eye checkup just 'cause I was having headaches," Connor Johnson says. "And I was vomiting too, so we just went in to they eye doctor to get checked. And he scheduled an MRI for the next day, and that's what diagnosed me."

The diagnosis is something no 13-year-old should ever have to worry about.

"I was pretty much in shock, because I would have never thought that I would have got cancer," says Connor Johnson. "But, yeah, I just really couldn't grasp my mind around it."

Connor Johnson had medulloblastoma, the most common form of brain cancer in children.

His parents say they were just as shocked as he was, but they had little time to consider the implications of their youngest child having cancer.

"I mean, it was – it came on so fast that there was no planning," Connor's father, Curt Johnson, says. "There was no thinking. It was just we knew we had to do it, you know, to try to save his life. So we just went in with the mindset of, OK, one step at a time. Brain surgery."

And that's how the most terrifying and painful time in the Johnsons' life began.

"Well, the brain surgery, I think it was six hours. And after that, I think a couple weeks later, I went to proton beam," Connor says. "And we did 30 sessions of that. And then after that we did chemo for 46 weeks, and we'd go, like, every week for that. And it's been pretty tough, but [I've] gotten through it."

But there were times Connor Johnson questioned whether he could get through it.

"Well, going into surgery, they said it was, like, a 1 percent chance of dying. And at that time, I thought that I could – I could die," Connor Johnson says. "But I haven't really thought that I was going to die. I thought that I'd get through it, but I was – I was never sure."

Fear of the odds, however small, loomed large for Connor Johnson's parents too – even as they tried to distract him from them.

"Well, I think any parent will tell you that they'd trade places with the kids –their kid in a heartbeat," Curt Johnson says. "I mean, you wish you could be in their place and feel their – feel the pain instead of them. But it's – it's pretty emotional. You try to, you know, I used humor a lot to keep them upbeat and positive. And you try not to show your emotions and cry and stuff in front of them as much as possible, but there's times when you do. But you just try to keep an upbeat, positive attitude, and just wish for the best."

Dr. Shakila Khan is a pediatric oncologist at Mayo Clinic's Rochester, Minnesota, campus. She was part of Connor's medical team there.

She says extensive research and great participation in clinical trials have drastically improved the numbers for childhood cancer outcomes over the years. But she says doctors like her have also come a long way in learning how to treat the patient and not just the disease.

"I mean, we treat the child as a whole," Dr. Khan says. "I usually tell the parents that we are part of the same team, and are, you know, they are part of our team. It is a multidisciplinary team, and we also include them so that we can take care of the child as a whole, not only for the chemotherapy."

"And attitude makes a big difference," says Dr. Khan. "I've seen – I've been doing it for a long time. Positive attitude helps."

But staying positive while going through such a traumatic time can be difficult for the patient and the parents.

"When you hear those four words: your child has cancer, you life just comes to a screeching halt," Sherrie Decker, co-founder of Brighter Tomorrows, an non-profit that provides support and resources to families dealing with pediatric cancer treatment at Mayo Clinic, says. Matter of fact, when the doctor tells you those four words, you don't hear anything the doctor is saying for the rest of that particular conversation. Everything is a blur. It is your worst nightmare. And when all you know of cancer is death, you think immediately that's what your child is going to go through, and that's where our minds go right away. But that's not always necessarily the case."

Decker knows the experience all too well. She went through it with her daughter, Shanna, close to 20 years ago.

"It's very true that when you look out the window and you watch the rest of the world moving on, just the cars moving down the street, the people moving through the courtyard, you think 'how can they go on with their life when our life has come to an absolute standstill,'" Decker says.

She says it's a lonely time. That's why she and four other mothers of kids with cancer started Brighter Tomorrows.

"And what we learned is that even though it was hard fort the parents, we had to provide that – that hope for that child, because they're always looking to the parents' eyes for that," Decker says. And, so, that's why it's really important for parents to have a place to go where they can seek re – you know, be re-invigorated a little bit by other families that are going through the same thing. And that's where the organization plays a big part is bringing another family into the room that's already done this and helping that family get a grasp on what they have to go through."

Brighter Tomorrows' work begins when these families need them most. The organization's first step is to provide a comfort kit full of things like snacks and toiletries they might need for long stays in the hospital, as well as some financial assistance during treatment.

They offer a safe place of understanding for parents to meet other parents, patients to meet other patients and even siblings to meet other siblings all going through the same thing.

There is a mutual understanding they can only find in others living under the same dark cloud.

"Yeah, because they'd, like, tell you their experiences, and it'd just help you through it a little bit," Connor Johnson says.

Perhaps, most importantly, Brighter Tomorrows hosts monthly events for the kids going through treatment to look forward to.

"You know, I mean, it always helps if you, you know, have things to look forward to," Dr. Khan says. "But kids are very resilient. I have to tell you, they just deal with things much better than adults."

Curt Johnson thinks Brighter Tomorrows' method of supporting families has made a profound difference for his family.

"It probably, you know, the treatments and everything would have been the same," Curt Johnson says. "But the positive mindset was definitely strengthened by going to Brighter Tomorrows and just being able to talk to other people that are going through the same thing you are – the same fears and emotions and hopes."

For Curt and Connor Johnson, it's been a daunting journey through treatment. But they have had little victories along the way to celebrate: each one making the effort to stay positive a little bit easier. They believe it was part of a cycle in which the positivity led to more victories to celebrate.

Connor Johnson made it through brain surgery. Then, after 30 session of cutting-edge proton beam therapy, Connor Johnson got to ring the ceremonial bell, signifying the successful completion of his specialized radiation therapy.

"It kind of surprised him how many people were there, but ringing the bell, I mean, was pretty emotional," Curt Johnson says.

Then, instead of doing things other kids his age were doing, like going to school, playing baseball, or hanging out with his friends, Connor Johnson pushed through 46 weeks of chemotherapy.

And after more than a year of treatment, Connor Johnson is now cancer-free and heading back to school with big plans for his future.

"I'm thinking of being in the medical field, and because people don't realize that life is so precious," Connor Johnson says. "And, yeah, I'm just think that I want to help people later in life."

"Grasp every day like it could be your last, because [for] a kid going through cancer, it may be their last," Curt Johnson says. "But just be positive about things. You know, hug your kid. That's first and foremost. Just hug them and love them."

Click here to learn more about Brighter Tomorrows.