-

Science Saturday: A new era in migraine care

For the millions of people who have migraine, the search for pain relief can feel like a nightmare game.

“Spin the wheel, see what drug you land on, and just try it. That’s the trial-and-error approach that we have had to use in migraine,” says David Dodick, M.D., a neurologist at Mayo Clinic's Arizona campus.

The World Health Organization ranks migraine as the third most prevalent medical condition in the world. In the U.S., migraine affects 38 million people at an annual estimated cost of more than $20 billion. The impact of migraines is amplified by the fact that people generally start experiencing attacks at a young age.

“Migraine affects people during the prime of their lives — while they’re trying to get an education, build a career and raise a family. And those effects extend throughout people’s lives,” Dr. Dodick says.

But new understanding of the biology underlying migraine, and the development of therapies developed specifically to treat and prevent the disorder, are changing migraine care.

“It’s a brand-new era. We’re about to see a plethora of mechanism-based, disease-specific therapies become available over the next few years,” Dr. Dodick says. “With this range of options in our therapeutic arsenal, I’ve never been more optimistic for patients.”

Mayo Clinic is at the leading edge of these efforts, participating in the design and data analysis of clinical trials for the news classes of migraine medication, such as research in Neurology, JAMA Neurology, JAMA and Cephalalgia in 2018. In the laboratory, Mayo Clinic is using advanced brain imaging to develop biomarkers for classifying migraine, a notoriously subjective disorder. Mayo Clinic neurologists also led the trial that resulted in approval of a noninvasive neurostimulation device to prevent migraine attacks.

The cornerstone of this new approach is precision medicine — tailoring diagnosis and treatment to the individual to optimize care.

“We are in a huge paradigm shift. For patients, that will mean more effective treatment options and less burdensome side effects,” says Amaal Starling, M.D., a Mayo Clinic neurologist. “It’s exciting to be involved as a clinician and a scientist, and it’s also an exciting time for patients.”

Engineering targeted solutions

Perhaps the biggest challenge of migraine treatment has been the dearth of disease-specific therapies. For years, migraine treatment relied on medications developed to treat other diseases, including epilepsy, hypertension and depression. “Although these medications were approved for migraine treatment, they weren’t based on any brain mechanism related to migraine,” Dr. Dodick says.

The triptan class of medications, which was developed in the 1990s specifically for migraine, was engineered to constrict blood vessels around the brain. At the time, migraine was thought to be caused by abnormal dilation of those blood vessels. But subsequent studies have shown that’s not the case.

“It turns out the mechanism for which these drugs were engineered is neither relevant nor necessary,” Dr. Dodick says. In addition, because triptans constrict blood vessels, they can’t be prescribed for people with significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

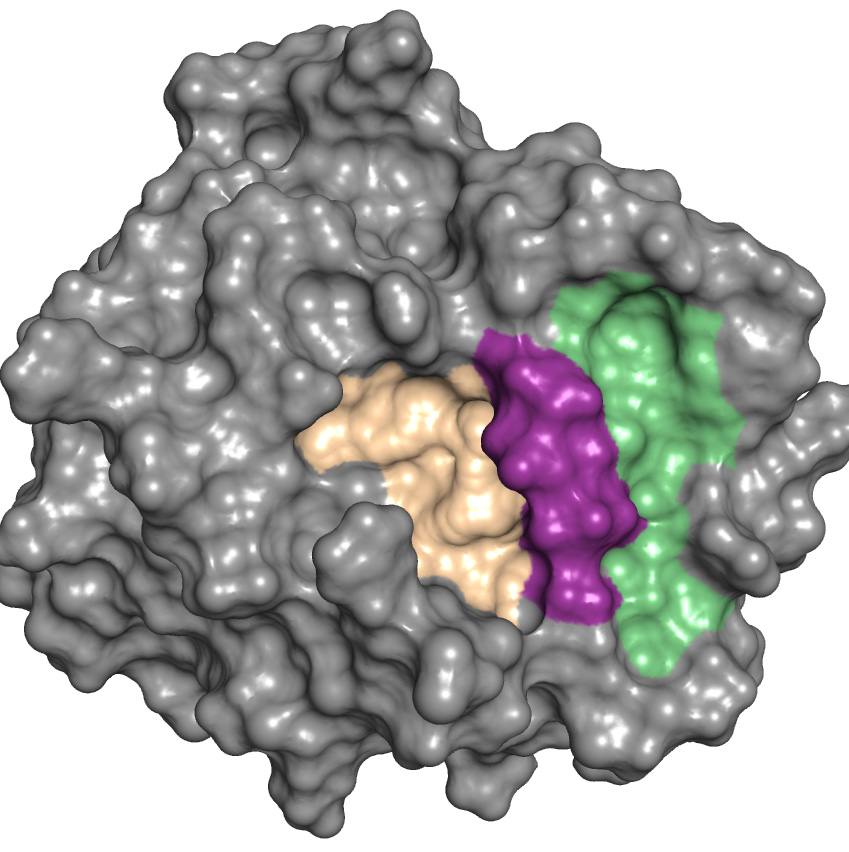

The new classes of migraine therapy target certain neuropeptides, known as "CGRP" and "PACAP."

“As our understanding of the underlying biology of migraine has come into much sharper focus, we’ve identified these neuropeptides that appear to play a pivotal role,” Dr. Dodick says.

To learn more about individual migraine triggers and treatment responses, Mayo Clinic has launched a multicenter registry of migraine patients in the U.S. The first registry of its kind, it includes multiple patient data points, as well as blood samples and an imaging bank where MRI and CT scans are uploaded. A second, international registry, started in Australia and the U.K., is set to expand to other countries.

“Over the next three to five years, we expect there to be a number of new, mechanism-based therapies that have different targets for individual patients,” Dr. Dodick says. “We don’t have to waste time with trial and error, and expose people to medications that aren’t going to be effective. That’s precision medicine.”

MRI that captures pain

Pain is real but subjective. Unlike a broken limb, you can’t take a picture of it. Nevertheless, at Mayo Clinic, imaging studies are revealing objective clues for diagnosing, treating and predict outcomes for people with migraine.

“Imaging is one way that we might identify additional subtypes of migraine beyond those commonly recognized,” says Todd Schwedt, M.D., director of Mayo’s Neuroimaging of Headache Disorders Laboratory on Mayo Clinic's Arizona campus. “Our current, subjective classification of migraine doesn’t identify all the subtle differences that exist among individuals with migraine.”

The Neuroimaging of Headache Disorders Laboratory is using functional and structural MRI to develop objective biomarkers for the classification of headache disorders. Currently used only for research, the MRI studies eventually may move into the clinical domain.

Functional MRI measures brain activity by detecting changes associated with blood flow. The headache researchers use this tool to assess how people process pain. With functional MRI data and machine learning techniques, the researchers have developed biomarkers that distinguish between people with migraine and healthy controls.

“We can look at the functional MRI and tell you with greater than 80 percent accuracy whether that MRI belongs to somebody who has chronic versus episodic migraine or chronic migraine versus a healthy control,” Dr. Schwedt says.

Structural MRI measures factors such as brain shape, and the volume and thickness of various brain regions. In a study based on structural MRI data, the headache researchers were able to cluster participants with migraine into two groups. During migraine attacks, people in the first group had more severe sensitivity to pain from events that normally wouldn't evoke pain, such as being lightly touched — than people in the second group. That condition is called "allodynia."

“The presence or severity of allodynia could be considered when defining migraine subgroups,” Dr. Schwedt says. “It’s been suggested that allodynia might affect migraine treatment response and disease prognosis, and our study suggests that it affects brain structure. The goal of all of these studies is to identify additional subgroups who have different prognoses or different likelihoods of responding to migraine treatments.”

Noninvasive prevention

People who live with migraine face a terrible dilemma: Take daily medication to prevent attacks and put up with side effects, such as nausea and fatigue, or stop taking the medication and dread the next attack. Less than 20 percent of people with chronic migraine are able to adhere to preventive medication for more than a year.

A neurostimulation device approved by the Food and Drug Administration offers another option. Using the principles of electromagnetic induction, the device transmits an electrical signal across the scalp and skull, and into superficial layers of the brain to alter the electrical environment.

“The brain of a person with migraine is hyperexcitable. In preclinical studies, we demonstrated that single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces brain hyperexcitability,” Dr. Starling says.

The device, previously approved for treating migraine attacks, can be used at home to prevent migraine with aura or migraine without aura. In the Mayo-led trial of the device for preventive treatment, people with chronic migraine administered four pulses twice a day for three months. Nearly half of the study participants had a reduction in their number of headache days of greater than 50 percent. There were also significant reductions in disability and in the number of days of acute medication use. Side effects were rare and mild: lightheadedness, tingling and ear-ringing. Full results can be found in Cephalalgia, published in May, 2018.

“This has been a life-changing experience for some of my patients, who have been able to stop taking some of their oral medications,” Dr. Starling says. “Usually, we prescribe separate medications for headache prevention and for acute treatment. That can be cumbersome and even confusing. Having one treatment option for both, with minimal side effects, is really attractive.”

Migraine affects more women than men. Mayo Clinic also is studying the use of the neurostimulation device in pregnant women with migraines.

One reason Dr. Starling chose to subspecialize in headache disorders is that she experiences migraines, as do several family members, including her husband and son. “There is definitely a stigma associated with migraine and a myth that somehow migraine isn’t real. That myth needs to be broken,” Dr. Starling says. “People with migraine aren’t weak. They have a real neurologic disease, which we are starting to objectively measure and which we can treat.”

-- Barbara Toman