-

Research

(VIDEO) From 125 fractures to the front lines of discovery: A Mayo Clinic resident’s unbreakable journey

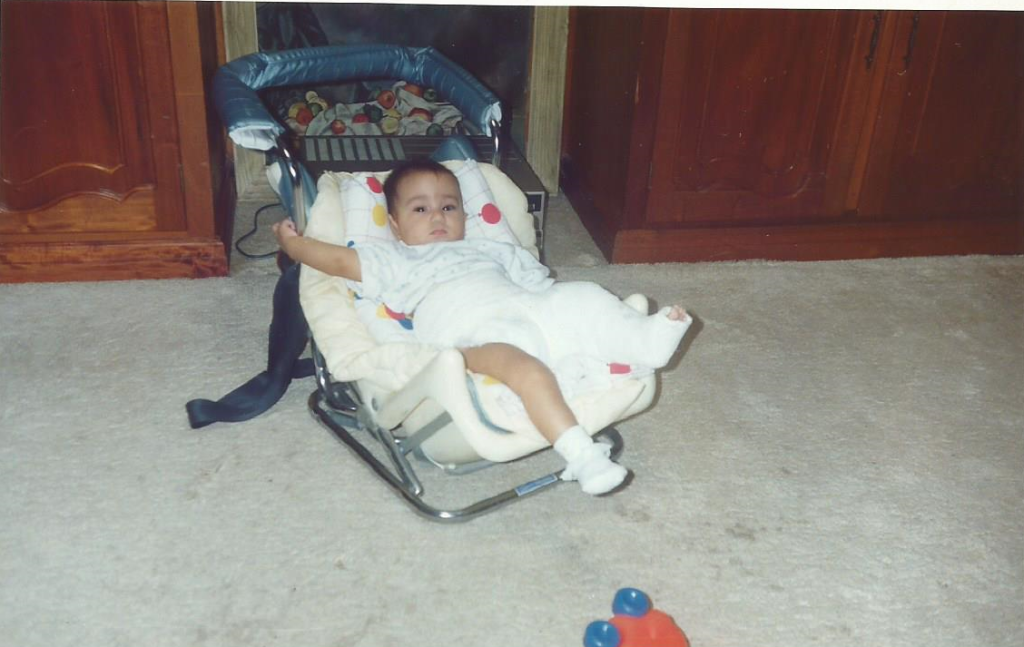

Dr. Ethel Aguirre Flores broke her first bone before she learned to walk. Since then, she has endured more than 125 other fractures — femurs, arms, ribs and vertebrae. Her medical chart includes 41 surgeries and six metal rods that hold her limbs together.

Her most recent fracture happened just months ago when she broke her toe while dancing. Not long before that, her femur snapped while she was simply walking.

But through it all, her determination, perseverance and commitment to helping others have remained unbreakable.

Watch: A Mayo Clinic resident's unbreakable journey

Journalists: Broadcast-quality video pkg (4:25) is in the downloads at the end of the post. Please courtesy: "Mayo Clinic News Network." Read the script.

Born with osteogenesis imperfecta, a rare genetic disorder also known as brittle bone disease, Dr. Aguirre Flores is now completing her residency in medical genetics and genomics at Mayo Clinic.

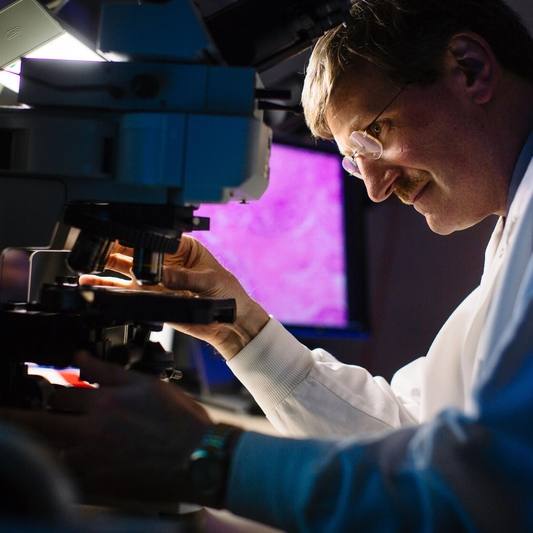

She came to Mayo specifically to study under one of the leading physician-scientists in the world focused on treating brittle bone disease at the molecular level. Dr. David Deyle, a clinical geneticist, has spent nearly 30 years studying the condition's genetic underpinnings and building the expertise needed to do what medicine has never done: develop a therapy that repairs it at its source. In addition to leading research, Dr. Deyle devotes most of his time to patient care, seeing nearly 30 patients with rare genetic disorders each week.

"Our goal is to correct the underlying genetic defect of osteogenesis imperfecta," Dr. Deyle says. "That means going directly into the genome, because you can't transplant bone stem cells. You have to repair them at their source."

Dr. Deyle is developing gene therapy to target the genetic mutation that disrupts collagen, the protein that gives bones their strength. The mutation produces a faulty form of collagen, which leaves bones weak and prone to fractures.

Dr. Deyle's team is pursuing two primary approaches. One uses gene editing, such as CRISPR, a tool that precisely cuts and modifies DNA, to eliminate the faulty genetic instructions. The other uses a small molecule therapy to strengthen bone density without altering DNA. Both approaches are inching closer to clinical trials.

"We can do this in the lab," Dr. Deyle says. "The challenge is delivery — getting the therapy directly into the bone."

That same precision guides the team's work across a range of rare conditions. One project involves classical Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a connective tissue disorder marked by fragile skin and poor wound healing. Dr. Deyle's team is using a combination of gene and cell therapies to give patients a second working copy of the gene they're missing. The modified cells are then reintroduced into the body to aid healing at the site of injury.

Another effort targets neurofibromatosis, a disease that causes tumors to grow along nerves. Dr. Deyle's team was the first to use a viral vector to deliver a key therapeutic protein. The method, which relies on a modified virus to transport treatment directly into cells, could help advance gene therapies for other rare conditions.

While the science is groundbreaking, the stories behind it are equally compelling. Some of the most determined minds behind this research in Dr. Deyle's lab know these conditions firsthand, including Dr. Aguirre Flores. She's the third person with brittle bone disease to train under his guidance.

"People with this condition know what it means to face setbacks," Dr. Deyle says. "That gives them a focus you can't teach. You can see it in Dr. Aguirre Flores — she's a fighter, and she pours everything she has into this work because of what she's lived through."

Dr. Aguirre Flores grew up in northern Mexico, the only daughter in a family of four children. Her parents encouraged her to chase every dream.

"They would always let me know anything's possible," she says. "You can do anything you want."

She swam competitively, earning medals despite broken ribs. She painted with casts on her legs.

At age 8, she met a care team in Texas that changed her view of what care could be. That's when she knew she wanted to become a doctor.

"They saw me as a child first, not just a diagnosis," Dr. Aguirre Flores says. "That changed everything."

Now, she brings that same perspective to her own career.

"I know what these children are going through. I want to help children with congenital disorders as a whole and help them live their childhood to the best," Dr. Aguirre Flores says.

In June, she will graduate from Mayo Clinic's Medical Genetics and Genomics Residency and begin a new role as a pediatric geneticist in Texas.

"I hope that my story brings hope and inspires others to not put limits on themselves," Dr. Aguirre Flores says. "And to always go after your dreams."