Neurosciences

April 29, 2024

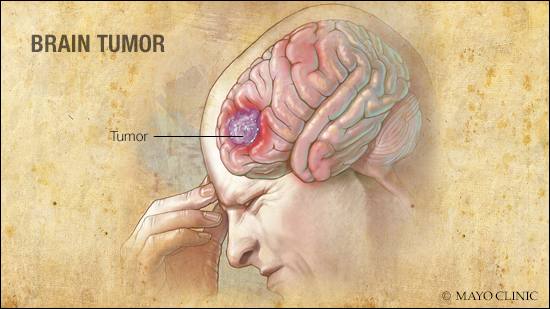

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I have been diagnosed with a brain tumor and advised to have radiation therapy. I'm very nervous about this and the risks[...]

March 2, 2013

February 27, 2013

February 21, 2013

January 25, 2013

January 10, 2013

December 10, 2012

December 5, 2012

Explore more topics

Sign up

Sign up

Mayo Clinic Connect

An online patient support community