I was 33 when I first began experiencing aches and pains that led me to the doctor. It was 2003. I was never married, never pregnant, generally healthy and living life to the fullest. I didn’t expect a cancer diagnosis.

The doctor told me I had stage 4 gynecologic cancer. Cervical or ovarian cancer? They couldn't be 100% sure, as medical technology was not as advanced back then. Tests seemed to indicate cervical cancer, so I was given the choice of radiation therapy or a hysterectomy.

After some soul-searching — and an appointment with a fertility specialist about freezing my eggs — I decided there were other ways to become a parent and opted for surgery.

When I woke up after surgery, I was told cancer cells were "everywhere" — and doctors still couldn’t confirm where the cancer had started. My care team recommended radiation to target cervical cancer and chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. I accepted their recommendations.

In 2003, getting information about my diagnosis and support from other patients was difficult. The internet was only 10 years old, and no in-person support groups existed.

Health care professionals also didn't know as much as they do now about the long-term side effects of cancer treatments. While my care team warned me that radiation could cause a secondary cancer, they didn’t mention other treatment side effects such as chemo brain or neuropathy, let alone discuss survivorship care.

I began seven weeks of daily pelvic radiation and had several chemotherapy drugs, including cisplatin, carboplatin and taxol. After treatment, I underwent scans every three months for a year and then was released back to "normal" life. Only I wasn't the same. My taste was altered, my sense of smell was off, I tingled in my hands and feet, and sometimes I forgot why I had walked into a room.

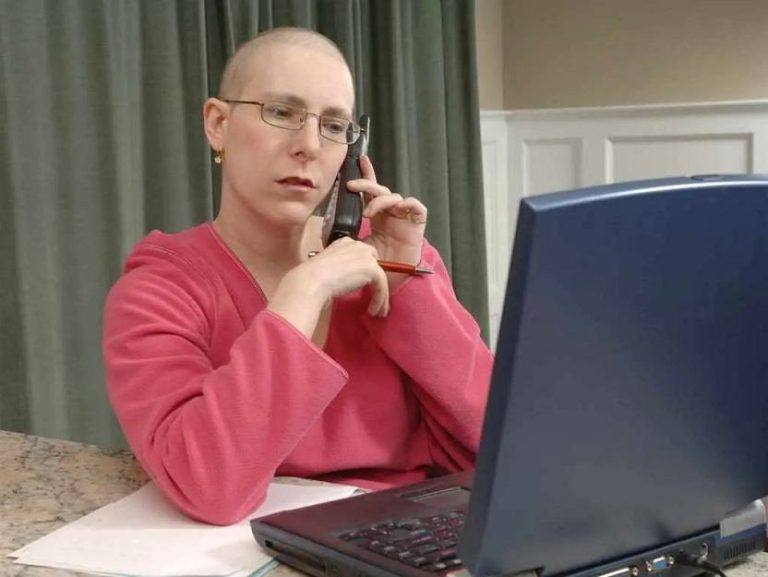

Two years later, the cancer came back. Technology led to a definitive diagnosis: ovarian cancer. With a better understanding of what was happening to me, I began more chemo – and a healthcare career. Today, I work in communications at Mayo Clinic and use my experiences to help others navigate their healthcare journeys.

Here are the lessons I’ve learned as a two-time cancer survivor:

1. Get a second opinion.

"You can have a second opinion if you want," said the doctor who initially diagnosed my cancer. Of course, I wanted a second opinion. I also got a third and a fourth opinion.

I will always advocate for another opinion. It's valuable to hear what another physician thinks and learn if alternative treatment options exist, such as a newer therapy, a less-invasive surgery or a clinical trial.

Take time to weigh your options. Although I ended up having the treatment that the original surgeon recommended, I did it on my terms: at a time I chose, with a doctor I was more comfortable with. Having a say in my care plan made a difference in my outcome. I had confidence in my team and their knowledge and understanding of my goals for therapy. This allowed me to walk through treatment with a more positive attitude.

2. Ask questions. And keep asking.

I was surgically induced into menopause in my mid-30s and received no education about what to expect. There was no discussion about how to cope with hot flashes or night sweats. No one mentioned how a lack of estrogen would affect my blood pressure, libido and sexual health. I felt lost trying to navigate things I didn't even realize were related to my cancer treatment. So, I asked questions. And I kept asking.

I encourage you to ask your care team these questions:

- What type of cancer do I have? Understanding your cancer and its genetic characteristics is essential when discussing therapies.

- What treatment do you recommend — and why?

- How long will treatment last?

- What side effects — such as hair loss, neuropathy and loss of smell — are most common with this treatment?

- How will you know if the therapy is working?

- If you are advised to have surgery, ask: Am I a candidate for minimally invasive surgery? Do I need a partial or total hysterectomy or an oophorectomy?

- Am I a candidate for any clinical trials?

- What would you do if this were your loved one?

I would advise against asking questions about outcomes and the risk of recurrence. Refrain from dwelling on what if or when. Focus your energy on what you can do today. But if you have questions, reach out to your care team. And if you don’t get an answer, ask again.

3. Be open to new treatments. And know that it’s OK to say no.

In 2014, the day after Thanksgiving, I developed abdominal pain that suddenly began in the late afternoon and increased in intensity through the night. A visit to the emergency room and a CT scan found nothing. Six months later, it happened again. Two weeks after that, it happened again. Over the next year and a half, I had various tests and MRIs and saw gastroenterologists, gynecologists, oncologists, radiologists and nutritionists.

Today I continue to be plagued by mysterious abdominal pain at random times, and I still have no answers other than scar tissue.

I have learned that the brain-gut link is significant. Stress exacerbates these pain episodes. While I cannot eliminate all stress from my life, I have found ways to cope by being open-minded. I have embraced integrative therapies including acupuncture, massage and dry needling. Last year, I began exploring meditation. I now have six meditation apps on my phone that I cycle through daily, and I have tried online health coaching. I also began to say no. Some alternative therapies were suggested for my pain that I am not comfortable with — yet. Maybe one day. In the meantime, no thank you.

I've also begun saying "No, not today" to things that may increase my stress. Instead of accepting another meeting request, I suggest another day. I ask my spouse to drive our child to the orthodontist.

Do what you can when you can. If you feel compelled to try something, go for it. And if not, say no.

4. Talk — and listen — to other survivors and advocates.

As a cancer patient, it's sometimes hard to feel in control of what's happening to you. Your body reacts to drugs in ways you can't necessarily predict, so getting intel from others who have "been there, done that" can help you plan.

I knew I wanted a wig, but my oncologist couldn't share much about when the drugs would affect my 'do. When I expressed my angst to the wig stylist, I learned a valuable tip — when your hair hurts, it's time. He was right. One day in October, my hair suddenly felt like it was on fire, and that night it hurt to sleep with my head on a pillow. My hair began falling out two days later.

After receiving an injection post-chemotherapy to help stimulate white blood cells, another cancer survivor told me: "You need to rest and drink lots of fluid. You're going to feel like you have the flu." I wasn’t worried. Although my appetite wasn't good, antiemetic drugs and antiacids had kept me out of the bathroom after chemotherapy, and I was still working.

I should have listened. Within 24 hours after the injection, my body ached terribly and I could barely walk from the bedroom to the living room without resting. The next time, I was prepared. I hydrated well the night before, made a pot of soup and armed myself with a heating pad.

5. Stay positive and learn about new opportunities

Having had a recurrence, I always have some level of fear. My anxiety is heightened at certain times of year — typically around the anniversary of my initial diagnosis — and any time I have abdominal pain.

I see a team of experts who help me manage the challenges associated with growing old as a cancer survivor: a primary care physician, a women's health expert, a gynecologist, and a lifestyle medicine specialist. They help manage issues related to menopause, like elevated blood pressure and cholesterol, overactive bladder and weight gain.

Although there isn't a diagnostic test for ovarian cancer, some ovarian cancers produce tumor markers, so I have blood drawn annually to check for changes. My numbers were significantly elevated when I was first diagnosed and at the time of my recurrence.

I now only have an MRI if I feel unwell. This is a blessing, as "scanxiety" is very real.

Recently I chatted with a neighbor who is being treated for pancreatic cancer. "How long does it take to not think about cancer every day?" she asked. "Everyone is different," I said. "It took me about 10 years after my recurrence." It wasn't 24/7, but there were days when I had so many thoughts swirling in my brain that I couldn't breathe.

Then one day, you realize it's been a month, two months, six months. I realize as I write this that I made it past the anniversary of my initial diagnosis without thinking about it. But then I feel a pit in my stomach when I remember how long it's been since my last scan.

Though I cannot predict the future, I try to take my own advice. I read articles and ask questions of clinicians and researchers about new treatments on the horizon and clinical trials that might be worthwhile for me to join. There have been significant advances in cancer care in the past two decades — from treatments targeting cancer cells' genetic characteristics to immunotherapies like CAR-T cell therapy. While I hope I will never need them, I am confident in the people at Mayo Clinic working every day to find a cure for cancer. My job is to help bring awareness to their work and stay positive, even when I find myself playing "What if?"

Learn more

Learn more about ovarian cancer and find an ovarian cancer clinical trial at Mayo Clinic.

Join the Gynecologic Cancers Support Group on Mayo Clinic Connect.

Also, read these articles:

- "Ovarian cancer is hard to detect, but new and better treatments are improving survival"

- "Faye Belvin: Living a healthy life, thanks to a phase I clinical trial"

- "Dear Mayo Clinic: Ovarian cancer symptoms and treatment options"

- "New chemotherapy approach for late-stage cancers"

- "Removal of both ovaries in younger women associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s"