-

Multidimensional neurosurgeon

Editor's Note: This article is the second in the Young Innovators series, originally published in Mayo Clinic's Alumni Magazine. Each article features Mayo Clinic trainee inventors and explores their journeys as biomedical entrepreneurs. All of these trainees say their goal was to improve health care for patients.

When he was a resident in the Department of Neurologic Surgery at Mayo Clinic in Florida, William (Bill) Clifton III, M.D., was disheartened by some aspects of surgical training.

“Cadavers are expensive to purchase and store, limited in supply and usefulness, not available for pediatric training, not used in all countries, and variable in quality — especially tissue quality,” he says. “My dad was an electrical engineer, so we had design-and-build projects going on around the house. Engineering, materials science and math have always been fun to me. I read some blogs and manuals about 3D printing and decided to create tools we could use in neurosurgical training.”

If you have an idea and believe in it, focus on how you can achieve it regardless of what others say is impossible.

Bill Clifton III, M.D.

Dr. Clifton took out a personal loan to buy a 3D printer that he installed at his home and then spent his free time creating models for surgical trainees. In two years, he created more than 1,200 adult and pediatric models, including skulls, brains, spinal cords, tumors and most organ systems. He has created models of specific patient pathologies to facilitate surgical planning, including a congenital spine abnormality and rare brain tumor.

Dr. Clifton’s creations are actually 4D, which means they change form in reaction to factors in their environment including heat, humidity and pressure. In this way, the models replicate the contraction, bending and breaking of human tissue. Dr. Clifton calls his models Biomimetic Human Tissue Simulators.

“4D printing has been around for only a few years,” says Dr. Clifton. “I saw a surge of papers about it in the aviation and automobile industries and wondered why we couldn’t apply it to the human body. 4D models allow us to see how the surgical landscape will change when we take specific actions.”

His first model was a vertebra that performed like bone when screws were drilled into it. Missing were ligaments, tendons, skin, fat and muscles. Dr. Clifton and his collaborator, Aaron Damon, a simulation technologist in the J. Wayne and Delores Barr Weaver Simulation Center at Mayo Clinic in Florida, delved into the organic chemistry of compounds,

inventing and patenting a new compound to represent those soft tissue structures.

“The full surgical models I’ve made for neurosurgery training cost $20 to $100 apiece, compared to $3,000 to $5,000 for a cadaver,” he says. “Physicians who evaluated them said they were as good as or better than a cadaver for training. The models also teach very subtle details of surgery that cadavers can’t, such as bleeding control and complication management. Our models are biodegradable, water soluble and nontoxic.”

Dr. Clifton has authored more than 50 peer-reviewed publications and submitted several patents for neurosurgical devices. Despite his focus in neurosurgery, Dr. Clifton worked with his colleagues in orthopedics, gastroenterology and transplant to develop training models.

Dr. Clifton says faculty members were ecstatic about the models because they accelerate the speed with which trainees are ready to perform in the operating room. And Dr. Clifton is ecstatic that surgical trainees don’t have to learn on patients.

“If you have an idea and believe in it, focus on how you can achieve it regardless of what others say is impossible,” says

Dr. Clifton, who is now completing a fellowship in complex surgery at Columbia University in New York City. “Just do it. I hope that, as the ultimate result of my belief in my idea, surgeons training today can acquire even better skills than their predecessors and that Mayo Clinic will be at the forefront of education, research and — most importantly — patient care.”

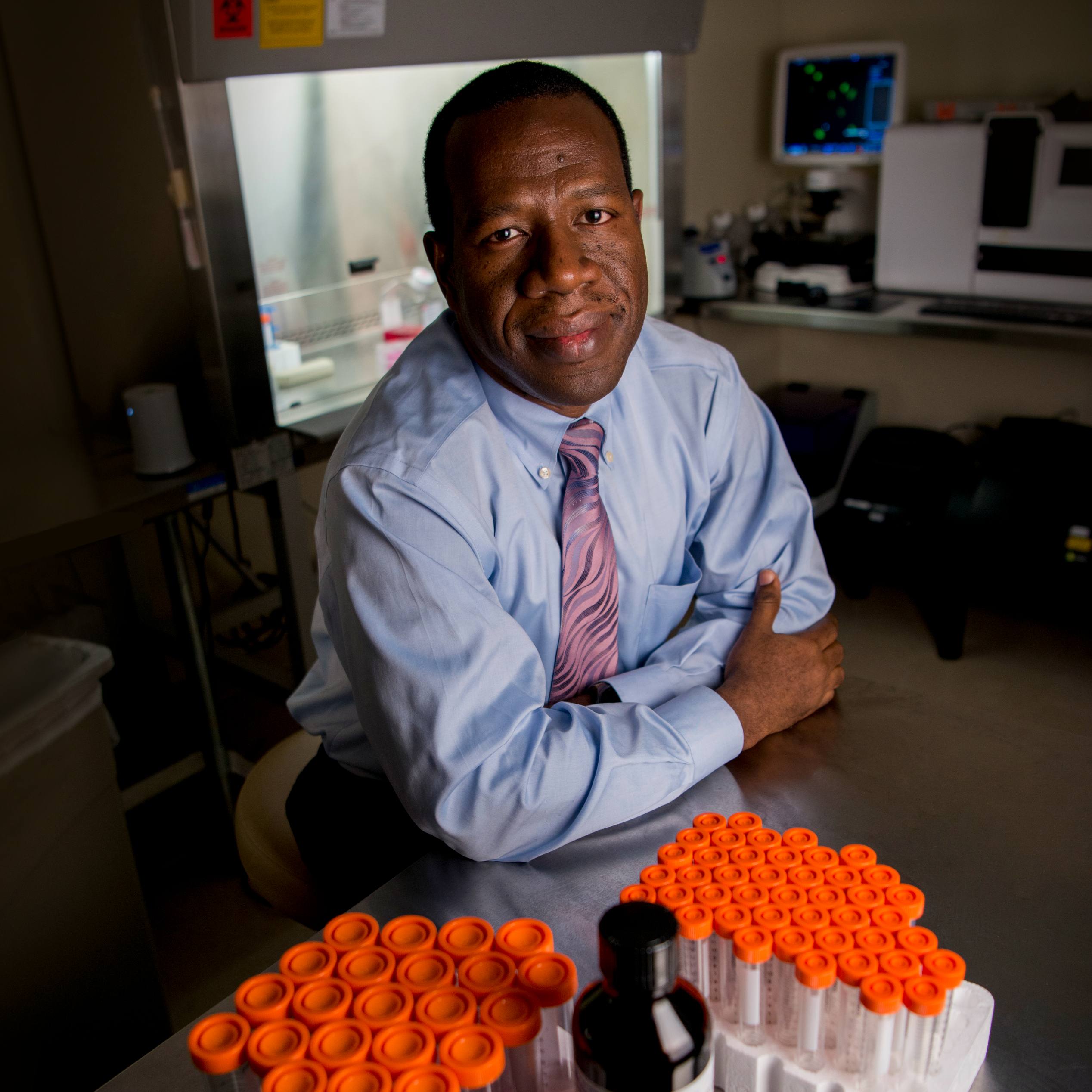

Alfredo Quinones-Hinojosa, M.D., chair, Department of Neurologic Surgery at Mayo Clinic in Florida and a William J. and Charles H. Mayo Professor, has assumed responsibility for Dr. Clifton’s lab.

###