-

Diversity

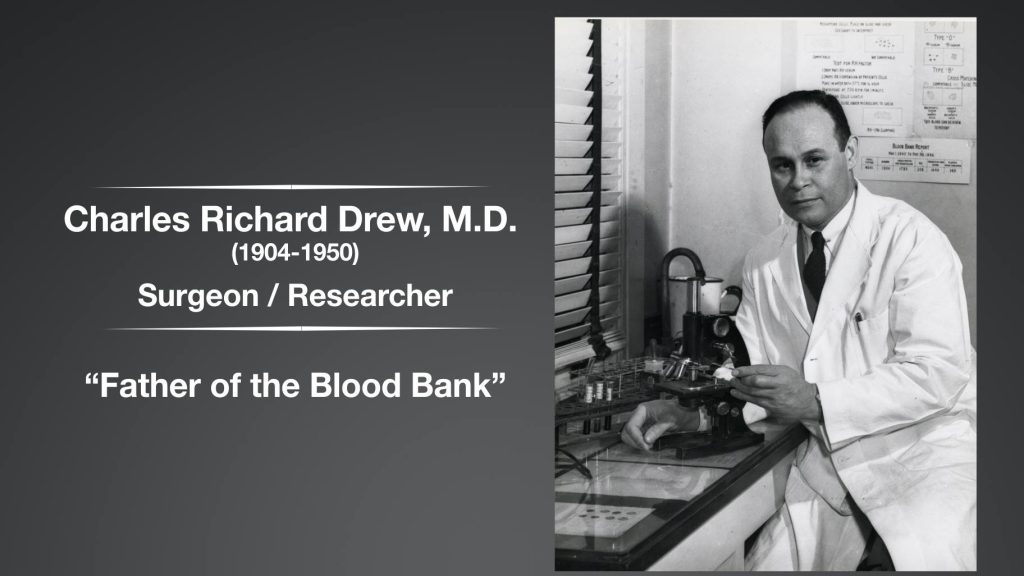

Black History Month: Honoring Dr. Charles Richard Drew

Each February, Black History Month is recognized to honor the many contributions of Black Americans and their role in U.S. history. Keeping with this year's theme of "Black Health and Wellness," the Mayo Clinic News Network recognized a pioneer in the field of medical science each week throughout the month.

This week, the Mayo Clinic News Network honors Dr. Charles Richard Drew.

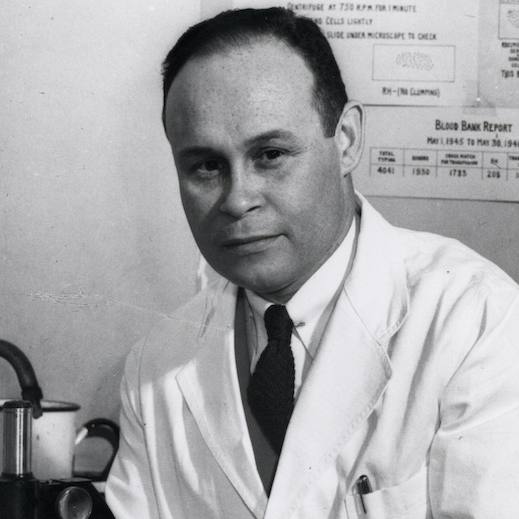

Dr. Charles Richard Drew was a renowned surgeon and medical researcher who pioneered methods for long-term storage of blood plasma. Called the "father of the blood bank," Dr. Drew is most notably known for organizing America's first large-scale blood bank and his work with the American Red Cross.

Born in Washington, D.C., in 1904, Dr. Drew was a top student and athletic child who was accepted to Amherst College on an athletic scholarship. Though a skilled and celebrated athlete, ultimately, a football injury and his sister's death during a city-wide influenza epidemic fostered his interest in medicine.

In 1933, Dr. Drew earned his medical degree at McGill University in Canada and began his remarkable, albeit short career.

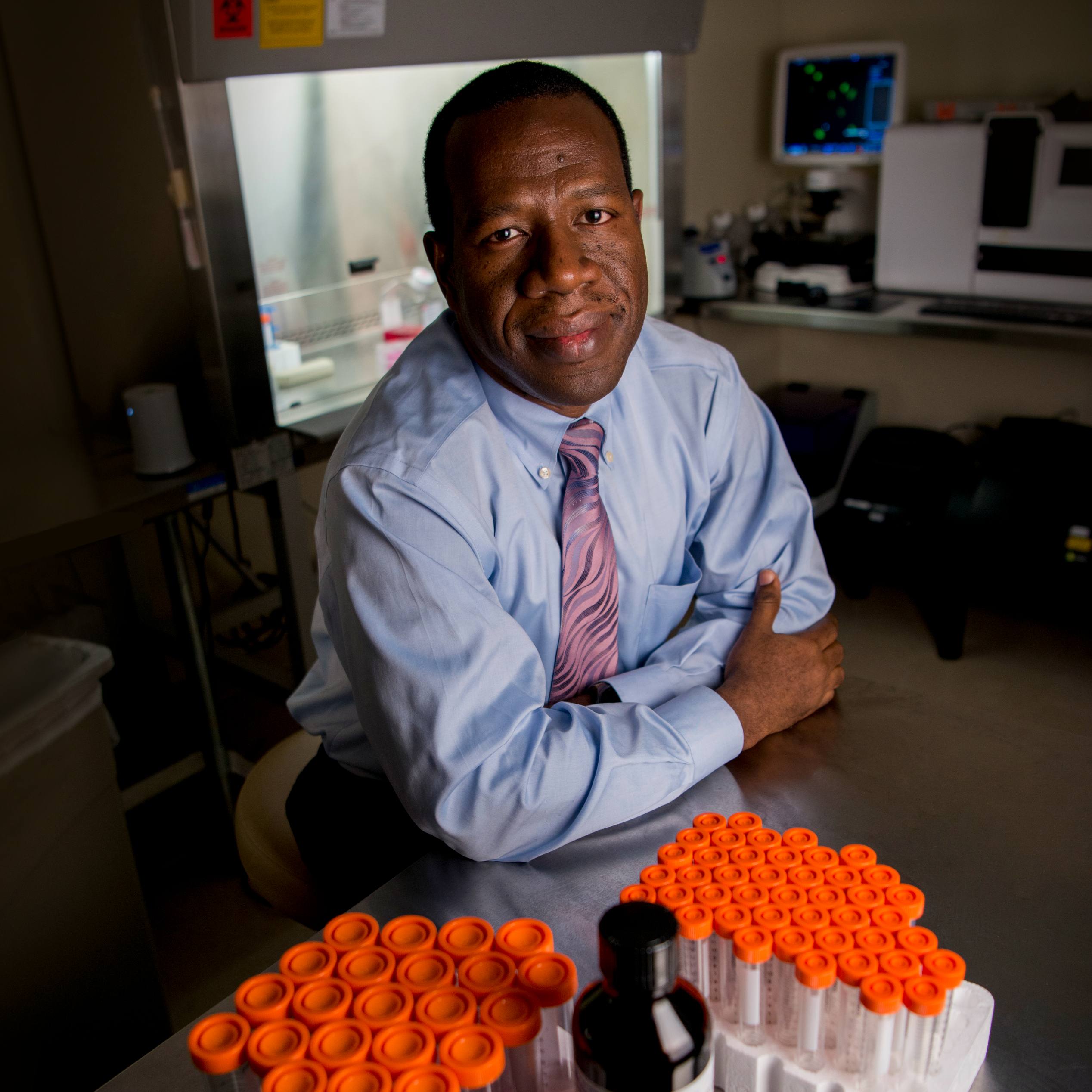

Dr. Jeffrey Winters, chair, Division of Transfusion Medicine, professor of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, offers this insightful look at Dr. Drews' work and legacy.

Dr. Charles Richard Drew is referred to as the 'father of blood banking' due to his critical contributions to the development of a safe, effective, blood collection system in the U.S. Prior to the early 1930s, whole blood was collected from donors for transfusion at the time it was needed. Literally, blood donors would be contacted at all hours of the day or night to come to a hospital to donate fresh blood, which was immediately transfused into the patient. In 1932 in the Soviet Union and later in 1936 at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and 1937 at Cook County Hospital in Illinois, donor blood was collected and stored prior to it being needed. This whole blood was then transfused to patients at those local hospitals, but was not shared outside of those facilities where it was collected.

In 1938, Dr. Charles Richard Drew, as part of his surgery training, studied in the laboratory of Dr. John Scudder, investigating shock and its treatment, including transfusion. At the time, whole blood could only be kept for two weeks because of the deterioration of the red blood cells. As part of his dissertation, Dr. Drew studied the storage conditions for blood, including investigating the effects of different anticoagulants, anticoagulant amounts, storage temperatures and storage containers, to determine the optimal conditions for storage.

His thorough investigation of the medical literature, practices among the early blood banks, and evaluation of multiple variables allowed for optimization of the collection and storage of whole blood. This resulted in Dr. Drew creating standardized processes for donor screening and testing for infectious diseases, blood processing and training of those collecting the blood. These standardized, reproducible processes have led to what we see today in blood banks around the world. As a result of his work, he received his Doctor of Medicine in 1940 for his dissertation 'Blood Banking.'

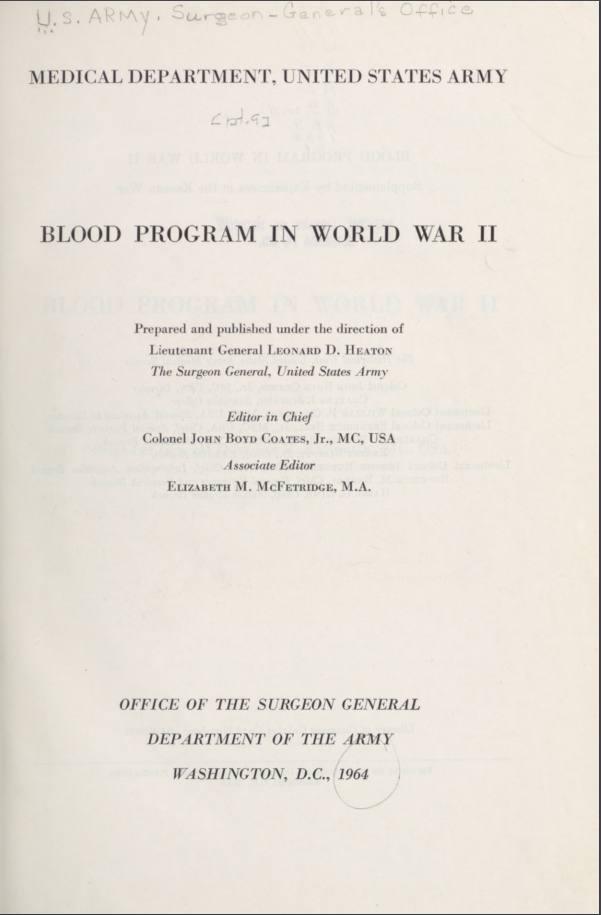

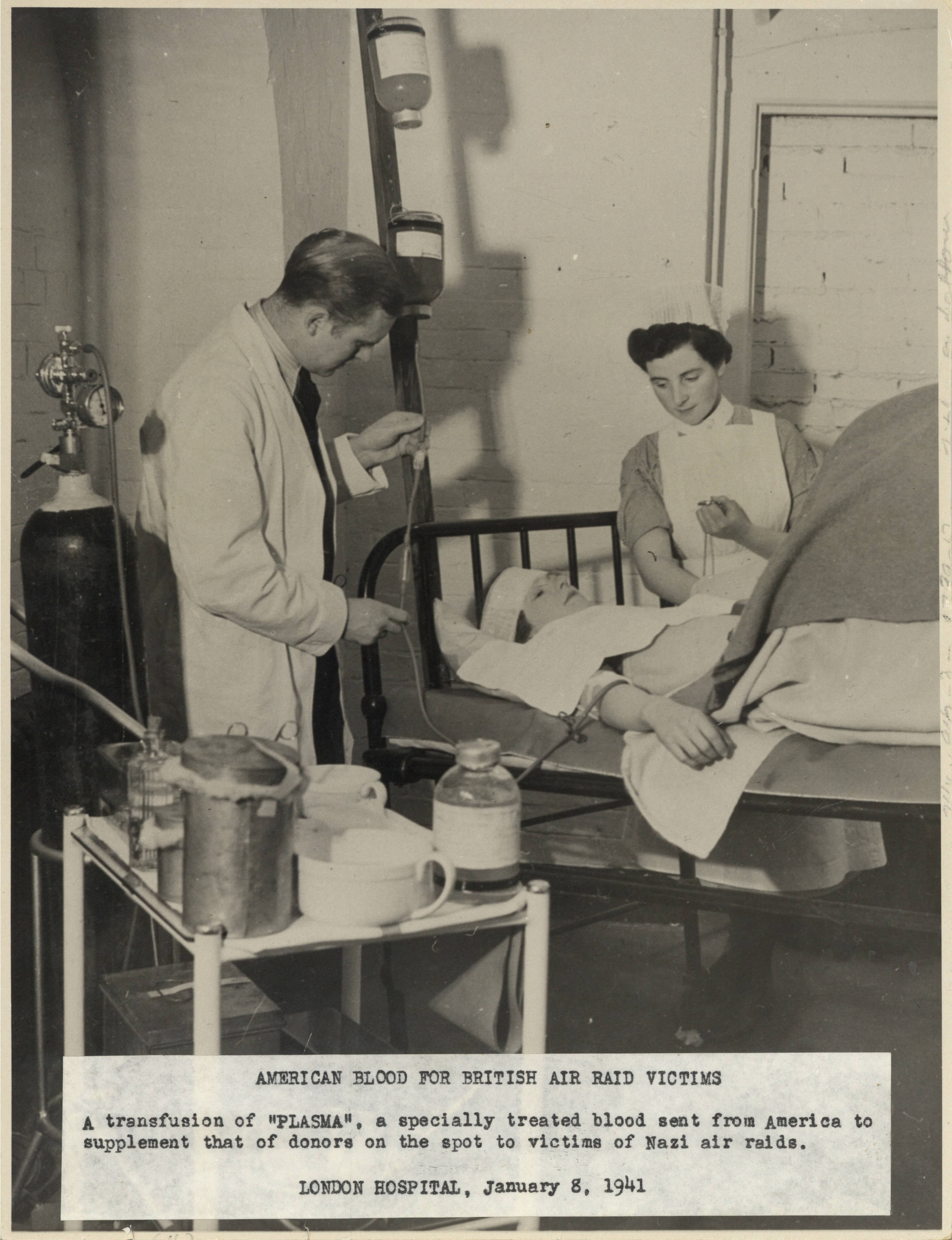

With the outbreak of World War II, there was a critical need for blood to support the war effort in Europe. The short shelf-life of whole blood led Drs. Drew, Scudder and E.H.S. Corwin to develop processes for the separation, preservation and storage of plasma, the liquid component of the blood, from the cells so that it could be shipped and transfused to soldiers on the battlefield. This led to 'Blood for Britain,' where nine New York City area hospitals collected blood, and separated and pooled the plasma, which was then bottled and tested for safety and shipped to Britain.

While plasma processed in this way is no longer used for transfusion, Dr. Drew’s work in this area was critical for saving countless lives during World War II and subsequent conflicts. When it ended in 1941, 'Blood for Britain' had shipped 5,000 liters of plasma to Britain.

Following 'Blood for Britain,' Dr. Drew created a program through the American Red Cross to collect and freeze dry plasma for use by American forces during the war. This became the National Blood Donor Service, which subsequently developed into the American Red Cross Blood Services which collects approximately half of the blood transfused in the U.S. today. Another component of this program developed by Dr. Drew was the creation of mobile blood collections that used trucks that would go to the donors to collect the blood. These mobile blood drives still exist today and account for a significant proportion of the blood collected in the U.S.

Dr. Drew’s critical research into optimizing and standardizing blood collections, creating large scale collection centers that provided blood products to the military, and the creation of mobile blood drives to encourage the blood donation by going to the donor are why Dr. Charles Richard Drew is considered the 'father of the blood bank.' While blood banks existed prior to his work, his efforts and innovation directly led to the blood collection centers we see today.

Dr. Jeffrey Winters, Transfusion Medicine

Download PDF: Blood Program in World War II, Medical Department, United States Army.

During that time, the blood donations and plasma for 'Blood for Britain' had been segregated by race at the insistence of the U.S. Armed Forces. This outraged Dr. Drew, an African American man who ultimately left his position as the first medical director at the American Red Cross and returned to Howard University as chief surgeon.

The American Red Cross reversed its decision of segregating blood in 1948, saying there was no medical or scientific reason to do so. Today, the organization continues to do important work of providing much-needed blood to hospitals to help ill or injured patients who may need a blood transfusion.

Dr. Charles Richard Drew died at the age of 45 from injuries sustained in a car accident in North Carolina while driving to a conference with three other Black physicians in 1950. He left behind his wife, Minnie, and four children.

Learn more about Dr. Charles Richard Drew and his work by checking out these resources:

- National Institute of Health: "The Charles R. Drew Paper."

- American Chemical Society: "Dr. Charles Richard Drew."

- National Inventors Hall of Fame: "Charles R. Drew Blood Plasma Preservation."

- The Journal of American History: "Red Cross, Double Cross: Race and America's World War II-Era Blood Donor Service."

- North Carolina Museum of History: "The Death of Dr. Charles Drew."

- Journal of the Medical Library Association: "Keeping Dr. Charles Richard Drew’s legacy alive."

- Digital Commons: "Great American Series: Dr. Charles Drew."

- Library of Congress: "Dr. Charles R. Drew: Blood Bank Pioneer."

- Singapore Medical Journal: "Dr. Charles R. Drew (1904-1950): Father Of blood banking."

- Arlington Historical Society: "The Hurdler: The Story of Dr. Charles R. Drew." (1969)

Related posts:

- Black History Month: Honoring Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller

- Black History Month: Honoring Dr. Marie M. Daly

- Black History Month: Honoring Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

- Inspiration and meaning of Black History Month for Mayo Clinic Staff

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: With a focus on health during Black History Month, a conversation on addressing disparities in care