-

Featured News

#FlashbackFriday 1952: No Substitute for Glass

This article first appeared Dec. 6, 1952, in the publication Mayovox.

“There is no satisfactory substitute for glass.”

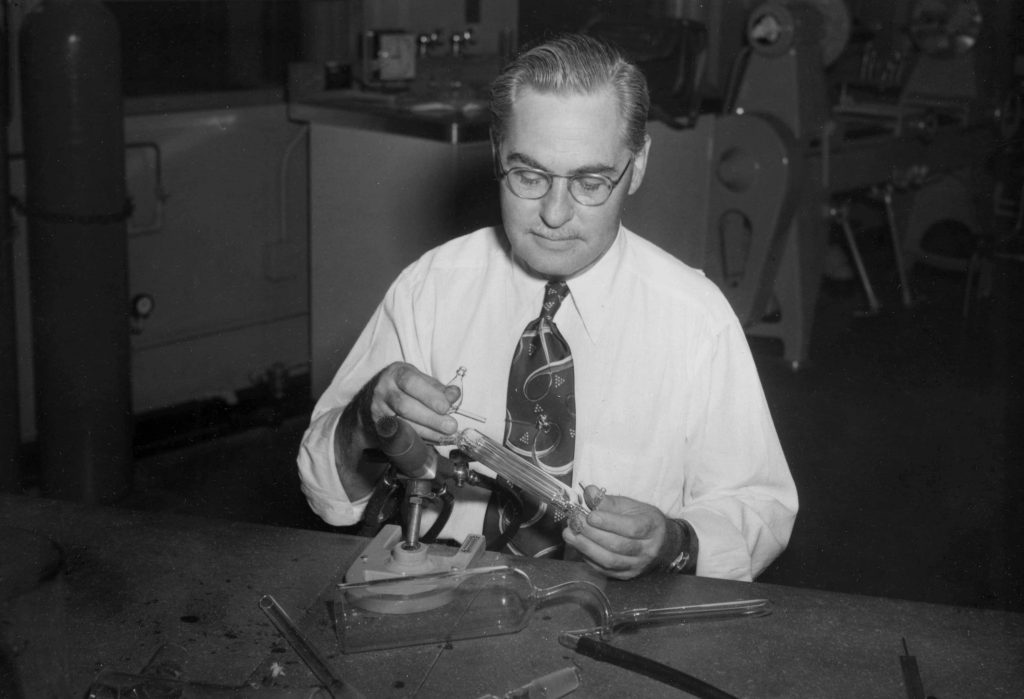

So says a man who knows a great deal about glass as it relates to the practice of medicine. So says Harry Nunamaker, chief of the Clinic’s Glass Blowing Shop. He is pictured below, and above with his colleague Robert Kidd to the left, working in the shop on the sixth floor of the 1914 Building.

Nothing was further from young Nunamaker’s mind than glass blowing, 30-odd years ago, when he was a teenager in Plainview, Minn. An exceptional trumpeter and accordionist, he inclined toward a musical career. After working for a time in Winona, he came to Rochester — that was in 1921 — to play in the old Garden Theater.

His sister, Mrs. Velva Erickson (former secretary to Dr. F. C. Mann, now secretary to Dr. L. A. Brunsting) suggested that he look into the possibilities for a young man at the Mayo Clinic. Harry talked with Dr. E. C. Kendall, went to work in the Chemistry Department.

From the beginning, the delicate, intricate research equipment —so much of it glass — fascinated him. He began “coming down nights and monkeying around.”

At Kendall’s suggestion, he went to the University of Minnesota, where he learned the technics of glass blowing from Edward Grienke. It should be added here that the Grienke-Nunamaker technics are being passed on to still another generation — Harry, Jr., is instructing in glass blowing at the University of Iowa, after having worked some time at the Clinic with his father.

Tools From Glass

It was 1922 when Harry Nunamaker finished his course at the University. In the 30 years since, with the help of a series of assistants, he has been absorbed in what can be done to shape hollow tubes — glass tubes — into tools for medical research.

(Could we digress here for a minute? Fired by Harry’s enthusiasm, we dug out some reference books on the history of glass. Among more important facts, we learned that seventeenth century American glass blowers showed a fine Yankee flair for combining the romantic with the practical. Seems that these boys would sit around the glowing glass furnaces of a winter evening to keep warm. To while away the time, they’d blow dainty little glass figurines and other trinkets. Then, come courting season, they would come bearing these as gifts to the eligible maidens of the community. This made almost impossible competition for the average bumpkin, whose best offer was a haunch of deer meat or hat full of wild berries. . . . And now back to the story. . . .)

Like other Clinic units, the Glass Blowing Shop has moved around a good deal.

Nunamaker’s first shop was in a little room on the eighth floor of the Zumbro Annex. After a couple of temporary moves, and for 20 years, the shop was located on the fourth floor of the ’14 Building, near the old Kendall laboratory.

The present shop is on the northeast corner of the sixth floor of the ’14 Building.

Two Parts To Work

Generally speaking, work at the Glass Blowing Shop is divided into two broad parts — repair and maintenance of standard laboratory glassware, and the making of specialized glass equipment for research.

The first part is pretty well self-explaining: It involves repairing “repairable” laboratory glass equipment such as test tubes, pipettes, flasks. There is a steady demand for such services.

The second, more difficult — and so more interesting — phase of the work lies in what Harry describes as “trying to ‘interpret’ someone’s need for specialized equipment, in glass.”

A typical example might go something like this.

A Clinic research man is working on an experiment. He finds that he needs a particular piece of glass equipment to obtain a certain result. He checks to see if the piece is commercially machined, and so readily available to hand or to order (often, these days, it will be).

Goes To Harry

But if the piece is not manufactured, our researcher roughs out a sketch of what it should look like, calls in Harry Nunamaker. With this, Harry goes back to the Glass Blowing Shop, works up a piece to fit the need. If it doesn’t accomplish what the researcher wants it to do, he and Harry go at it again. And again, and again, until it’s right.

Skill and experience, rather than elaborate equipment, are the keys to most glass blowing work at the Clinic. Most work can be handled with relatively simple equipment: high-temperature burners (Harry calls them “lamps”), reamers, files, tweezers.

There is larger equipment if needed. For work too large to be handled by hand “at the bench,” there is a glass lathe. This device performs the same service as a standard lathe in a machine shop, with the difference that a cutting flame replaces the regular “bit.”

The largest single piece of equipment is the annealing furnace. When glass tubing has been twisted, bent, blown and coaxed generally into the desired shape, it is under a “strain”. This piece of glass is placed in the annealing furnace, heated to a high temperature, slowly cooled again to room temperature. You know what “tempered” steel is? Pretty much the same purpose is served by the annealing process.

Almost all tubular glass used hereabouts these days is Pyrex, “hard stuff.” The range in diameter of tubing kept in stock is from one-eighth inch to four or five inches, which will meet almost any average request.

Craftsman At Work

A skilled craftsman can do fantastic things with glass.

He rotates the section of the tube to be shaped in the flame of the burner. When it has reached the consistency of thick honey, the glass blower can bend it into any desired shape. He can blow a large bubble, then blow a bubble within the larger bubble. He can stretch it, loop it, narrow it, snip it off with ordinary scissors.

The end result can, and often does, look like a modern art form. It is, however, an art form with a serious purpose — the creation of tools for laboratory men and women to work with.

A glass blower needs a number of skills and characteristics. He needs a feather touch in the blowing itself. He needs imagination, a flair for “seeing” what the end product will look like. He needs patience. But above all, he needs experience, to gain what Nunamaker calls “knowing what you can make glass do, and what you can’t. The basic feel of glass.”

Getting back to his original statement, Harry Nunamaker explains that while some plastics have been found useful in replacing glass for some purposes, “Glass remains the favorite. Many chemical solutions ‘attack’ metals and plastics; glass is impervious. You can heat and cool glass many times without damage. You can see into it. . . .”

A standard reporter’s question is: how much material is used in the course of a year? Not much, in terms of feet and pounds, Harry says. Because,

“You can do a great many things with just a short piece of glass tubing.”

You can, if you know as much about what you can make glass do, and what you can’t, as Harry Nunamaker.