-

Cardiovascular

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Vast Majority of People With Mitral Valve Prolapse Won’t Need Surgery

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I have been told that I have mitral valve prolapse, but I’ve never had any treatment for it. Will I eventually need surgery? Also, because of the condition I used to take antibiotics before going to the dentist, but my new doctor said that’s not necessary. What do you recommend?

ANSWER: The vast majority of people who have mitral valve prolapse do not require surgery. For some, though, surgery is needed eventually. To monitor your condition, you should have regular follow-up appointments with your doctor, along with imaging exams of the mitral valve. How often you need these appointments depends on the severity of your condition. Antibiotics before dental work no longer are recommended for people with mitral valve prolapse.

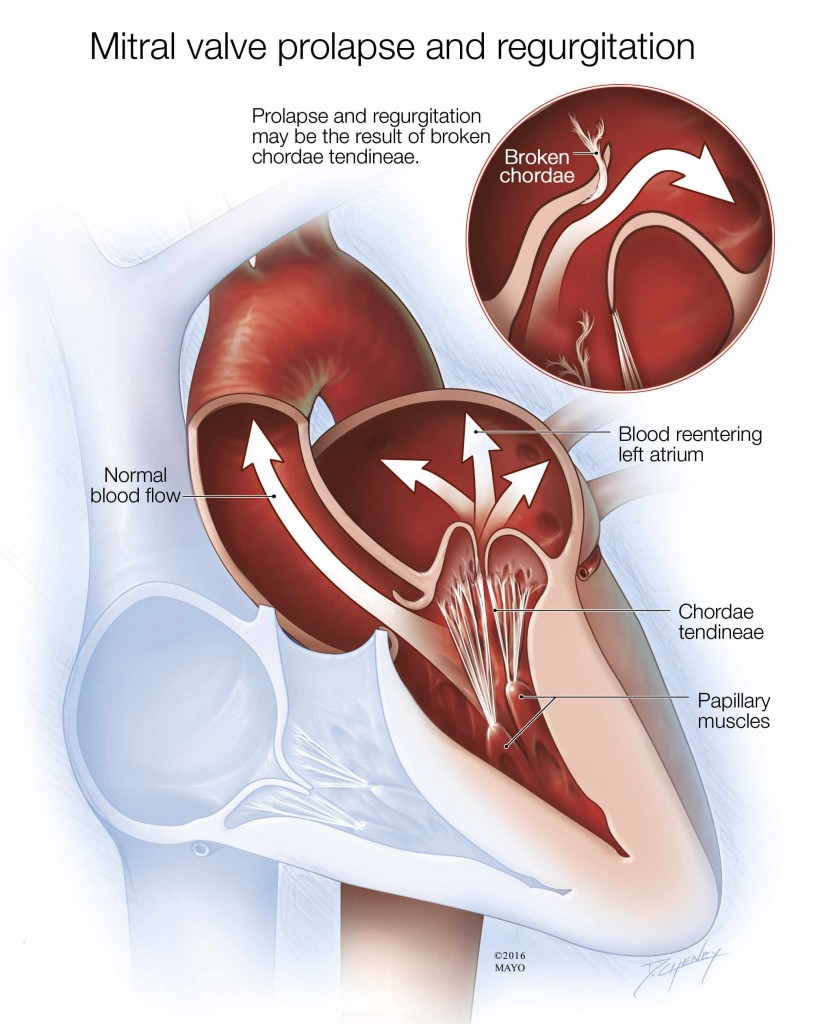

Your mitral valve is located between your heart’s upper and lower left chambers — the left atrium and the left ventricle. The valve is made up of two triangular-shaped flaps of tissue called leaflets. Mitral valve prolapse happens when the leaflets don’t close tightly together when your heart beats. During mitral valve prolapse, the leaflets bulge, or prolapse, into the upper chamber (left atrium) as the heart contracts.

Many people aren’t aware that they have mitral valve prolapse, because it often doesn’t cause any symptoms. It’s usually found on an exam that’s done for another reason. However, in some cases, mitral valve prolapse can cause blood to leak backward into the left atrium, a condition called mitral valve regurgitation. Although it doesn’t always lead to symptoms, mitral valve regurgitation may trigger symptoms such as a racing or irregular heartbeat, dizziness, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, fatigue or chest pain.

If you have mitral valve prolapse without mitral valve regurgitation, or if it is mild, treatment usually isn’t required. Your doctor likely will suggest you have regular follow-up exams to monitor your condition. Many people with mitral valve prolapse have these exams once a year.

You’ll also likely have an ultrasound examination of your heart, called an echocardiogram, on a regular basis. Echocardiograms use high-frequency sound waves to create images of your heart and its structures, including the mitral valve, and the flow of blood through the heart. How often you need an echocardiogram depends on the severity of your condition. It can vary from about every five years in mild cases, to every six months in severe cases.

Mitral valve prolapse usually does not get worse or cause other problems. If, over time, however, you develop severe mitral valve regurgitation, then surgery may be necessary. If left untreated, severe mitral valve regurgitation eventually can cause heart failure, preventing your heart from effectively pumping blood.

Surgery for mitral valve prolapse involves repairing or replacing the valve. For many people, repair surgery that preserves their own valve can effectively correct prolapse and regurgitation. If valve repair isn’t possible, then the damaged mitral valve is replaced with an artificial valve. The artificial valves are either mechanical or they are made from animal tissue.

Your second question about antibiotics is a good one. Doctors used to recommend that some people with mitral valve prolapse take antibiotics before certain dental or medical procedures to prevent an infection in the inner lining of the heart called endocarditis. That’s not the case anymore. According to the American Heart Association, antibiotics are no longer necessary for people who have mitral valve regurgitation or mitral valve prolapse.

If you haven’t already done so, talk to your doctor about how often you need to have follow-up appointments for mitral valve prolapse. If at any point you start to develop symptoms that could be related to the prolapse, make an appointment to see your doctor promptly. — Dr. Sorin Pislaru, Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota