-

Research

Progress in gene therapy offers hope for long-term knee pain relief

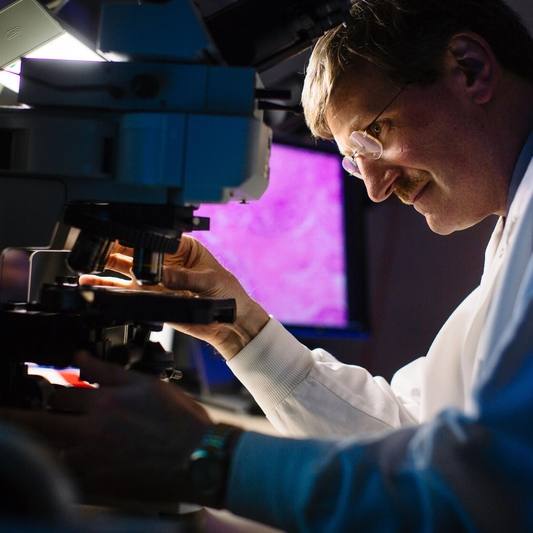

For nearly three decades, Mayo Clinic researcher Christopher Evans, Ph.D., has pushed to expand gene therapy beyond its original scope of fixing rare, single-gene defects. That has meant systematically advancing the field through laboratory experiments, pre-clinical studies and clinical trials.

Several gene therapies have already received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and experts predict that 40 to 60 more could be approved over the next decade for a range of conditions. Dr. Evans hopes a gene therapy for osteoarthritis — a form of arthritis affecting more than 32.5 million U.S. adults — will be one of them.

Recently, Dr. Evans and a team of 18 researchers and clinicians reported the results of a first-in-human, phase 1 clinical trial of a novel gene therapy for osteoarthritis. The findings, published in Science Translational Advances, demonstrated that the therapy is safe, achieved sustained expression of a therapeutic gene inside the joint and offered early evidence of clinical benefit.

"This could revolutionize the treatment of osteoarthritis," says Dr. Evans, who directs the Musculoskeletal Gene Therapy Research lab at Mayo Clinic.

In osteoarthritis, the cartilage that cushions the ends of bones — and sometimes the underlying bone itself — degenerates over time. It is a leading cause of disability, and notoriously difficult to treat. "Any medications you inject into the affected joint will seep right back out in a few hours," says Dr. Evans. "As far as I know, gene therapy is the only reasonable way to overcome this pharmacologic barrier, and it's a huge barrier." By genetically modifying cells in the joint to produce their own pharmacy of anti-inflammatory molecules, Evans aims to engineer knees that are more resistant to arthritis.

The Evans laboratory found that a molecule called interleukin-1 (IL-1) plays an important role in fueling inflammation, pain and cartilage loss in osteoarthritis. As luck would have it, the molecule had a natural inhibitor, aptly named the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), that could form the basis of the first gene therapy for the disease. In 2000, Dr. Evans and his team packaged the IL-1Ra gene into a harmless virus called AAV, which they tested in cells and then pre-clinical models. The results were encouraging.

In pre-clinical testing, his collaborators at the University of Florida demonstrated that the gene therapy successfully infiltrated the cells that make up the synovial lining of the joint as well as the neighboring cartilage. The therapy protected the cartilage from breakdown. In 2015, the team got investigational new drug approval to start human testing. But regulatory hurdles and manufacturing challenges kept them from injecting their first patient for another four years. Mayo Clinic has since established a new process for accelerating clinical trial activation that could help researchers launch studies more quickly.

In the recent study, Dr. Evans and his team gave the experimental gene therapy to nine patients with osteoarthritis, delivering it directly into the knee joint. They found that the levels of the anti-inflammatory IL-1Ra increased and remained elevated in the joint for at least a year. Participants also reported reduced pain and improved joint function, with no serious safety issues. Dr. Evans says the findings suggest the treatment is safe and may offer long-lasting relief from osteoarthritis symptoms. "This study provides a highly promising, novel way to attack the disease," he says.

Dr. Evans has co-founded an arthritis gene therapy company called Genascence to drive the project forward. The company just completed a larger phase Ib study and is in discussions with the FDA about launching a pivotal phase IIb/III clinical trial to evaluate the therapy's effectiveness, the next step before FDA approval for the therapy.

Review the study for a complete list of authors, disclosures and funding.

Additional resources: