-

Research

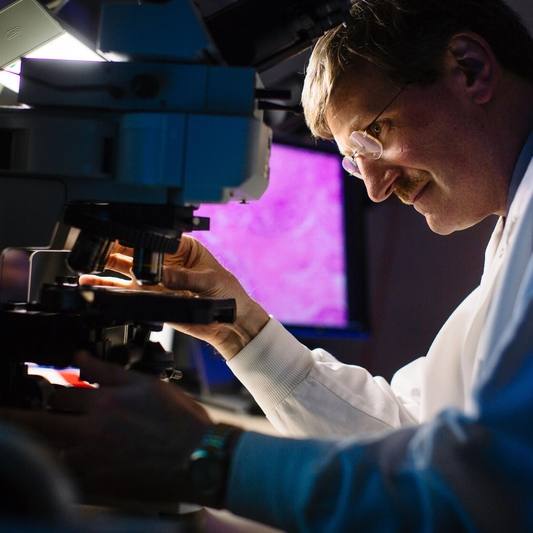

To combat heart disease and cancer, genomics researcher looks abroad

Genetic technology has the potential to significantly improve human health by improving disease risk prediction and guiding prevention strategies. The development of a new genetic test called a polygenic risk score is a major advance. Still, it may widen health disparities because such scores may not work equally well for different populations. Iftikhar Kullo, M.D., a cardiologist at Mayo Clinic, believes that global collaboration is needed to refine polygenic risk scores so they perform equitably across people from diverse groups.

Dr. Kullo recently authored a perspective piece in Nature Genetics, where he made the case for efforts to bring genomics to low- and middle-income countries. His argument is that the information gleaned from testing could not only benefit local populations but also many other groups around the world, including in the U.S. Here, he elaborates on this.

Q: You've noted that the disease burden worldwide is shifting from communicable diseases such as hepatitis and influenza to noncommunicable diseases such as heart disease and cancer. How can genetics address this shift?

Dr. Kullo: The shift from infectious disease to noncommunicable disease is part of the "epidemiologic transition." Famines and pandemics were once the leading cause of mortality, but fortunately, these were addressed by antibiotics, vaccinations and adequate food production. Now, we live longer and, as a result, are prone to developing other diseases like heart disease, diabetes or cancer. One of the ways that we can reduce the burden of these noncommunicable diseases is to employ better ways of predicting risk. For many of these conditions, we have existing tools for risk prediction, but they don't always perform as well as we would like them to.

Q: You are referring to a new genetic test called a polygenic risk score. Could you explain what a polygenic risk score is, and how it works?

Dr. Kullo: Genetically, humans are 99.9% similar. Our genome has three billion letters (A, G, T and C), and every 1,000 letters or so, there is a variation or difference between any two people. These differences, or variants, account for how we look or behave, how we might react to drugs, and our predisposition to different diseases. Polygenic risk scores add up information from multiple such genetic variants that affect our risk of developing certain diseases. Each variant is not very useful by itself, but if we combine the information from many — thousands or even millions of variants in some cases — we get useful and actionable information about disease risk.

Q: What is the limitation of polygenic risk scores? How could they widen global health disparities?

Dr. Kullo: Polygenic risk scores don't perform well across different genetic ancestry groups. Because the vast majority of genetic studies are done in people of European genetic ancestry, these scores don't work very well, for example, in people of African genetic ancestry. One way we can address that disparity is to increase diversity in our studies here in the U.S., but an even better approach may be to undertake a global effort, conducting this work in diverse regions across the globe. We know that using diverse sources of data will improve the performance of these scores for everybody.

Q: You wrote that African datasets are still a high priority for genomic studies. Yet, they are the least represented — less than 2% of human genomes analyzed so far are of people with African genetic ancestry. How can studying African genomes help advance our understanding of the genomic basis of common diseases in all people?

Dr. Kullo: Africa contains the greatest genetic diversity among the continents, accumulated over 300,000 years of human evolution. By studying people of African ancestry, we will learn so much more about human origins and genetics because we're all Africans, in a way — that's where Homo sapiens arose. That long evolutionary history means that African populations could yield more information about genetic variants associated with disease. And it's a chance to make up for this big disparity in the number of Africans in genomic studies thus far.

Q: What steps do you believe are necessary to achieve equity in the availability of polygenic risk scores to improve global health?

Dr. Kullo: We certainly need to increase the representation of minorities in genomic studies. Mayo Clinic is part of a large National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded consortium called eMERGE that is looking at polygenic risk scores for 10 common conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, breast cancer and prostate cancer. The consortium is committed to ensuring that at least half of the 25,000 participants across the country come from diverse groups.

It's important to learn about the spectrum of genetic variation in all of humanity, not just in one group. I believe that means going beyond our borders, helping other countries to set up infrastructure to generate their own genetic data and creating resources for data-sharing across the globe. It's not an easy task, but we have many elements in place, and I think it's doable.