Today is National Navajo Code Talkers Day - a day to honor the group of U.S. Marines who created a secret code credited with helping the U.S. win World War II.

At 94 years old, Peter MacDonald Sr. is the youngest of three surviving Navajo code talkers in the world.

He visited Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, Arizona to share his defining chapter in American history. MacDonald also made a personal plea for improving access to high-quality healthcare for people in his homeland, which he hopes will be part of his legacy.

Watch: Navajo Code Talker - Peter MacDonald, Sr.

Journalists: Broadcast-quality video is in the downloads at the end of this post (1:32).

Please courtesy: "Mayo Clinic News Network." Read the script.

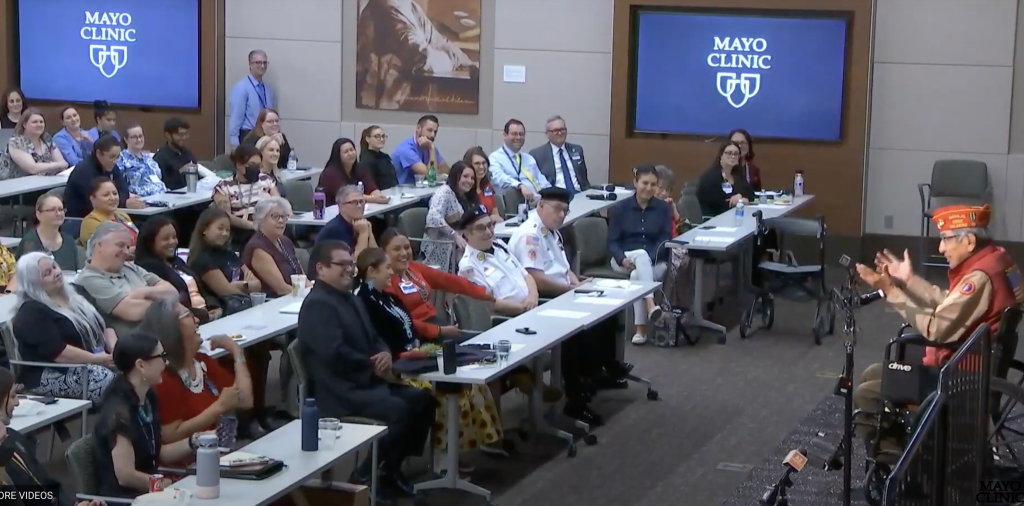

About 200 Mayo Clinic employees attended the special ceremony honoring National Navajo Code Talkers Day. Another 1,000 employees joined live online for the rare opportunity to step back in time and hear a firsthand account of events from the battlefields in 1942 that would shape American history.

MacDonald, now confined to a wheelchair, greeted the audience with a warm, energetic welcome and a touch of lightheartedness that brought chuckles to the crowd. If you want to keep a secret, MacDonald teased the crowd, "Just start talking to people in Navajo code," he said with a grin. "No one in the world will understand what you're talking about!"

Before MacDonald began his story, he wanted to deliver a message. MacDonald asked the audience for their support in helping achieve health equity in Native American communities. "On the Navajo Reservation, we have so many health problems," explained MacDonald. He admitted that his efforts which began in the 1970s as chairman of the Navajo Nation to eliminate health disparities have fallen short. "I still feel that even today if you read the news, or watch TV, you know there are a lot of illnesses on Navajos, like diabetes," said MacDonald. "It's high as opposed to what's in the rest of the country."

MacDonald shared his own experience of receiving medical care at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota 50 years ago. He was inspired by Mayo Clinic's multidisciplinary approach to medical care. "The doctor asked me a lot of questions, and then had me see three other specialists," said MacDonald. "The next day I went back and he had all the reports in front of him. He said 'Ok, this is how we are going to take care of you.' I will never forget that. We need that kind of care on the Navajo Reservation."

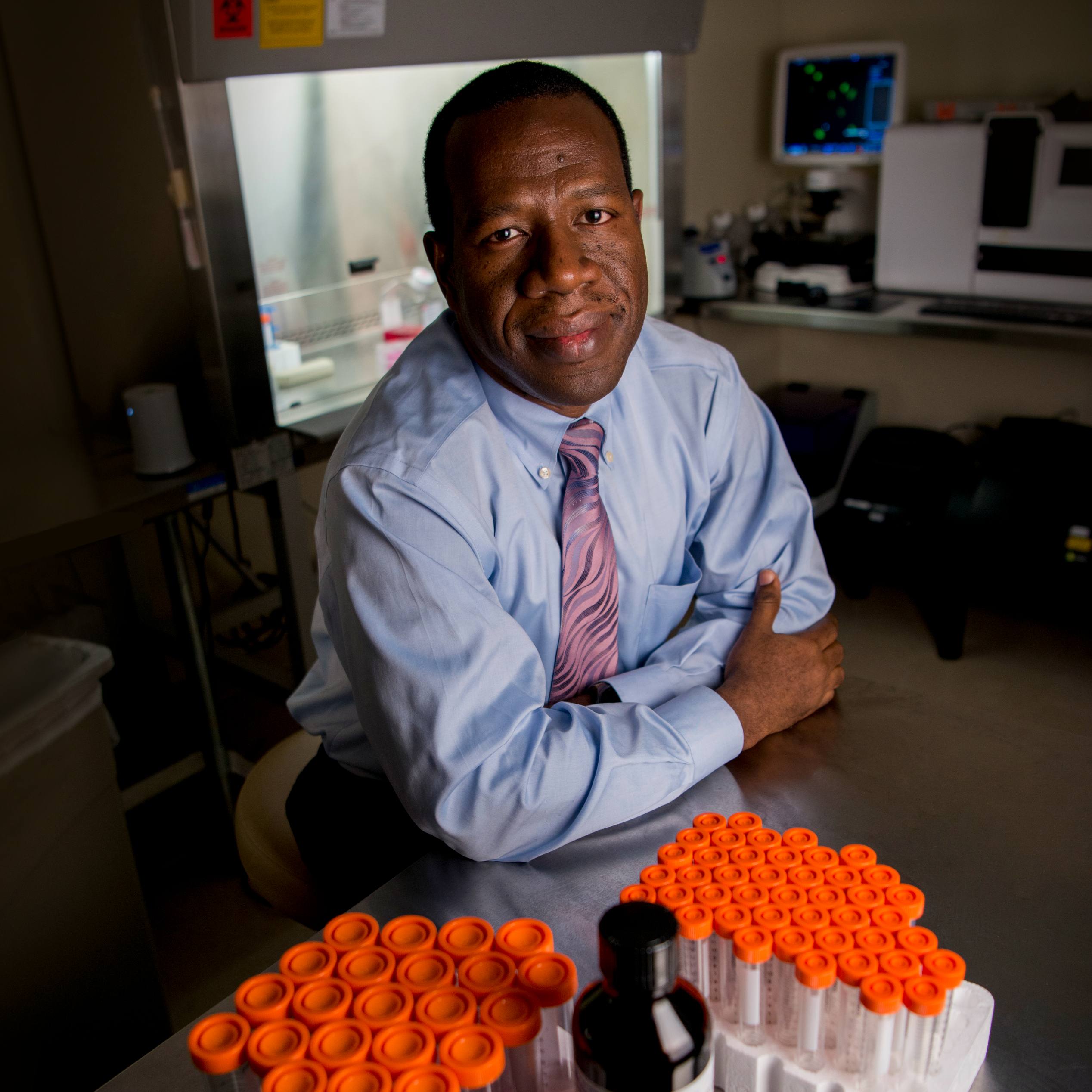

MacDonald applauded recent efforts by Mayo Clinic to eliminate barriers to healthcare for people in Native American communities with its new community outreach program. A year ago Silena Thomas began working as a Native American patient outreach navigator for Mayo Clinic. Silena was born and raised on the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona. Fluent in both English and Navajo, Silena works connecting American Indians and Alaskan Natives with lifesaving organ transplants at Mayo Clinic.

"Growing up on the reservation with my mom and grandma, I was the only person that could speak both languages. So everywhere we went, I was the translator, especially at medical appointments."

Silena Thomas, Patient community Outreach Navigator, American Indian and Alaskan Natives

Thomas has helped dozens of people navigate the maze of getting an organ transplant. "Many of the people living on the reservation don't have a phone, computer, or Wi-Fi to make appointments. Also, a lot of people don't have transportation. I help patients organize all those details so it's not so overwhelming," said Thomas. "Because I can speak the language and I understand the culture, patients feel more comfortable. It feels like home. For me, it feels like I'm talking to my mom or my grandma."

Robert's story

Robert Monroe and his wife Jackie live in a remote area with their children and grandchildren on the Navajo Reservation. Their small trailer has no air conditioning, a wood-burning stove for heat, intermittent cellphone service, and is miles from high-quality healthcare. Five years doctors told Monroe he would need weekly dialysis for a failing kidney. It was an hourlong drive to the closest dialysis center.

"Mosty of the time I just ended up hitchhiking to get to kidney dialysis."

Robert Monroe, Resident Navajo Nation

"It would take the whole day and I couldn't be there to take care of our home and our family," said Monroe. It is almost two years after Monroe's successful transplant. "I'm grateful to Silena, and the person who gave me this new kidney. I've been able to get back to work and take care of my family."

The top-secret classroom

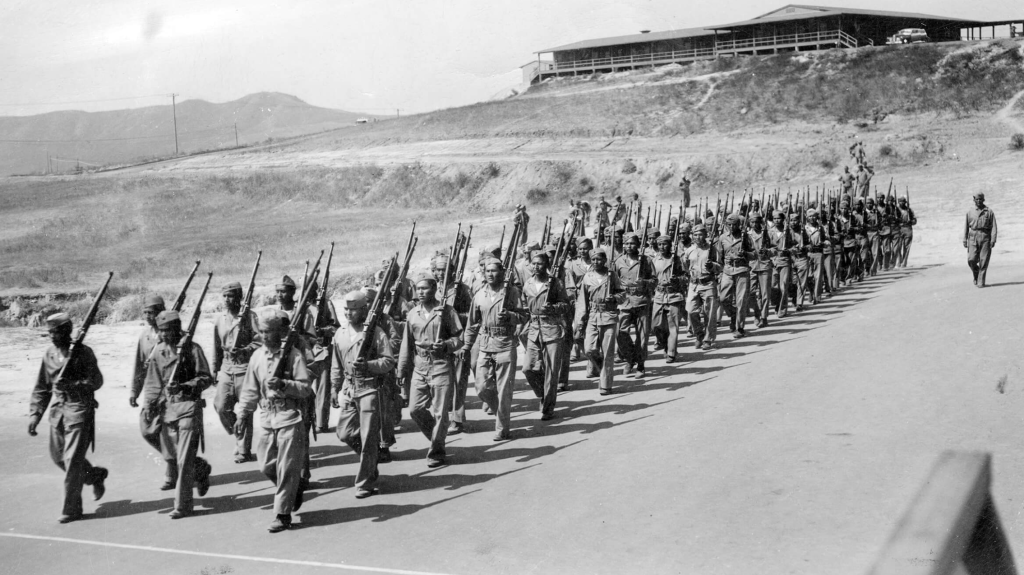

After MacDonald's plea for support for his homeland, he spent nearly an hour sharing a vivid account of how the code talkers used a secret code they created based on the complex, unwritten Navajo language. MacDonald described the top-secret classroom surrounded by armed guards and razor wire where the group of 29 Navajo service members converged to create the code.

"In that classroom, were tables with four chairs around each table. On the walls were huge blackboards with chalk and erasers," described MacDonald. "Now we're talking June of 1942. The Marine Corps Colonel looked at us and said 'Gentlemen of the United States Marines, are you ready to go fight a war in the Pacific? But before you do that, we would love for you to do something else first. We'd like for you to develop a military code using your own language.'"

"Are you ready to go fight a war in the Pacific? Before you do that, we would love for you to do something else first. We'd like for you to develop a military code using your own language."

Peter MAcDonald recalls the order by the U.S. Military in 1942

By the beginning of July, with part of the code created, MacDonald said they were given the order to find out of the code would work. "We're going to stop here. We're going to test this code," remembers MacDonald describing the Colonel's words. "You must develop an actual battle to see how your memory works under enemy fire. You can't write anything down because if you get shot the enemy will search you and find messages in your pocket. We don't want that," adds MacDonald.

The code was never cracked by the enemy. Historians argue the Navajo Code Talkers helped expedite the end of the war saving thousands of lives. It wasn't until 1968 the Navajo Code Talkers program was declassified by the military. Since then, the Navajo code talkers have drawn the attention of crowds eager to hear their war stories.

Thomas helped organize the event at Mayo Clinic in honor of National Code Talkers Day. "It's important for us to honor the contributions made by Navajos," said Thomas. "We have to preserve our heritage as we work together to improve the health of our communities."

Related posts:

Breaking barriers: Helping Native Americans in need get the gift of life

Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: Commitment to equity, inclusion and diversity

Save Lives: Become an Organ Donor